Voters Reinforce Republican Stronghold on State Board of Education

“Critical Race Theory” boosts multiple new conservative voices onto the board, including a participant in January 6 pro-Trump rally.

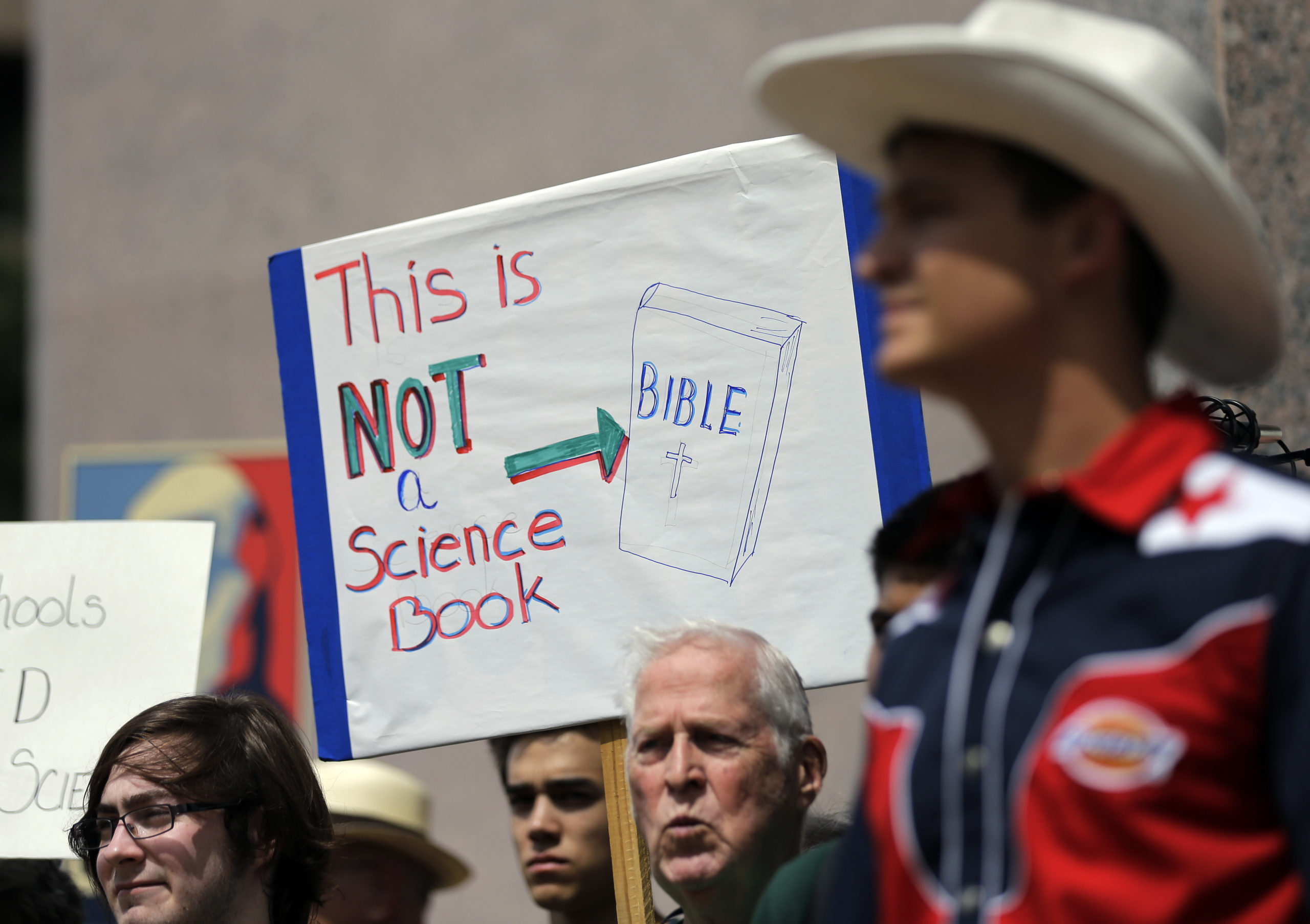

Republicans will hold onto power at the highest level of education policymaking in Texas after Tuesday night’s election. The election offered the first glimpse into the effects of the newly redrawn districts for the State Board of Education, in which all 15 seats were up for reelection. The new map, which includes nine firmly Republican districts, reinforces Republican control of the board as topics like critical race theory, book bans, and parental involvement in the curriculum have heated up along party lines.

Ten Republicans—including one participant in the January 6, 2021, rally in Washington, D.C., to stop the certification of the presidential election—and five Democrats are expected to take office after Tuesday’s election. That’s a net pickup of one seat for Republicans compared with the current state board.

“Yesterday’s election could have gone better for public education. But it also could have gone a lot worse,” wrote Texas American Federation of Teachers President Zeph Capo in a letter to members.

The State Board of Education—a separate entity from the Texas Education Agency, which oversees public schools and is responsible for standardized testing—has enormous power over what goes on in Texas’ more than 1,000 public school districts, including what more than 5 million students are taught. The board, made up of members serving four-year terms, sets curriculum standards and approves instructional materials, including textbooks. The body also has final say over charter schools that want to set up shop in the state. Despite this reach, the board has historically flown under the radar in elections—that is, until this year.

Education policy has lately become hotly debated in Texas. In May, a wave of conservative candidates took over school board seats in suburbs throughout the state, many under the banner of keeping critical race theory, or CRT, out of classrooms. CRT is an advanced academic study of how race is ingrained in society. It is not taught in Texas public K-12 schools.

In a call with the Texas Observer, Capo said that he expects conversations with the board about curriculum matters will likely become more difficult given the new slate. “It was already a contentious conversation,” Capo said. “And I do think it has the potential to cause further distraction from schools. … So much of what takes up time and space is just an exaggeration.”

At the state level, Governor Greg Abbott fueled the fire by signing a “critical race theory” bill into law, which severely limits the ways in which teachers can discuss race and racism in the classroom. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick has also promised to push forward a bill that prohibits discussion of sexuality or gender before a certain grade level. Earlier this year, the sitting State Board of Education postponed adopting new social studies standards after pressure from conservative powers to delay the decision, presumably in the hopes that Tuesday’s election would usher in a more conservative board.

In the March primaries, two incumbents on the state education board were knocked off by anti-CRT candidates. Four of the seats were filled by uncontested candidates before Tuesday night’s election—three Republican and one Democrat.

In District 2, the race that attracted the most donations by a wide margin, unsuccessful Democratic candidate Victor Perez, former school board member of the Pharr-San Juan-Alamo Independent School District, raised just under $166,000—a fairly high number compared to his Democrat peers. But Perez’s opponent, Republican LJ Francis, raised a whopping $407,107 in campaign donations. Francis took the seat after winning major support for his anti-CRT stance.

The winner in District 7, Julie Pickren, attended the January 6, 2021, rally in Washington, D.C, which led to what many describe as an attempted coup. At the time, Pickren was serving on the Alvin Independent School District Board, but she was voted out after the Brazoria County NAACP demanded accountability. Pickren’s victory, while somewhat of an outlier in the midterm election, reflects a growing cohort of extremist conservatives taking office.

Pickren’s campaign website includes a pledge to, among other things, follow the Texas Constitution and ban critical race theory from the classroom, despite the fact that the Abbott-led ban is already in effect. She amassed notable campaign support from deep conservative pockets like Richard Weekley, who donated $30,000, and Amanda Schumacher, who contributed more than $17,000 to Pickren’s campaign, as well as $75,000 to Abbott’s reelection effort.

Pickren gained support by centering parents’ rights in her campaign. She also touts school choice, writing on her LinkedIn, “It is a parent’s responsibility and right to choose the educational system that works best for their child and I will have Your Voice!”

Down the ballot, many Texans voted for school board races on Tuesday as well. Although school board trustees have decidedly less sweeping power than members of the State Board of Education, the races are crucial entry points for conservative political hopefuls. While a less dramatic wave than the one that overtook North Texas school boards in May, some conservative candidates were successful in local elections. In the Austin-area city of Round Rock, conservative newcomers backed by the One Family Round Rock PAC failed to win over voters. But in nearby Leander, an anti-CRT candidate unseated an incumbent.

As in May, the presence of big-money PACs elevated the often-sleepy school board races to new heights, boosting the profile of right-leaning candidates and ensuring that conservative talking points made it to the airwaves. Lawyer and election finance expert Jim Cousar said the PAC money isn’t entirely new to school board races. Teacher associations and groups looking to support candidates with infrastructure-related platforms have historically thrown money into these races.

“What’s different now is PACs getting into school board races with explicitly ideological agendas,” Cousar said.

Cousar added there’s a precedent in Texas for nonpartisan races becoming more and more politicized—and expensive—over time. In the 1980s, judicial races began to take on a more partisan tenor as certain candidates began to raise money to publicize their candidacy. Others soon had to follow suit to stay competitive.

“In school board races, we’re going to see a similar trajectory, where it gets expensive and it becomes viewed as a partisan job rather than a public service job,” Cousar said.

The new State Board of Education, as well as members of school districts throughout the state, have very real challenges to contend with, as low pay, harsh working conditions, and the pandemic exacerbate a statewide teacher shortage. A growing contingent of supporters for school vouchers could also affect public school funding models—and we’re likely to see more movement on this during next year’s legislative session.