State Calls Out Waco ISD for Disciplining Black Students Unfairly

A few years ago, Waco ISD had a serious discipline problem. More specifically, it had a problem with dispensing discipline. School police were giving out far too many tickets—in 2006-07, the district of fewer than 17,000 students handed out 1,070 tickets—principals were booting too many kids into alternative classes or suspending them, and African-American students were more harshly punished.

In 2012, the district won a $600,000 grant from the governor’s office to create a model program that could turn those trends around. Texas Watchdog‘s Curt Olson featured the “Suspending Kids to School” initiative in a story that year:

Under Suspend Kids to School, teachers receive training to better manage their classrooms, and leaders among students receive training in peer mediation and campus teen courts. The district also has a Saturday course to help parents address student behavior.

In the program’s first year, the district sharply reduced its ticketing, and principals started sending far fewer students into the alternative classroom. The timing coincided with the Legislature’s realization that school discipline was turning draconian all over Texas, funneling too many kids into a school-to-prison pipeline. Last year, the Legislature barred school police from ticketing students for minor misdemeanors. Waco ISD, as Texas Watchdog put it, became “ground zero for Texas student discipline reform.”

In a reminder, maybe, of just how long that reform can take, Waco ISD’s board heard recently that the district had been flagged by state regulators for some troubling discipline practices in the last school year. As the Waco Tribune-Herald reported:

[T]he district expelled 20 students for actions that are not considered expellable under the Texas Education Code, such as fighting and persistent misbehavior. Expellable offenses include possessing a weapon and selling drugs, among other misconduct.

The district also assigned a 5-year-old to the DAEP even though the minimum age is 6, the report said.

And the most systemic issue noted in the Texas Education Agency’s review, according to the paper: “About 60 percent of discretionary DAEP placements were black students, even though they make up about 30 percent of the student body.” Some things—like assault, drinking on campus or huffing glue—mean automatic removal to a disciplinary program. But in cases where administrators had some leeway in discipline, African-American students in Waco were pulled into disciplinary programs at more than three times the student average.

The report from TEA came from a routine check of school district data, designed to spot typos and faulty record-keeping. If Waco ISD confirms that its stats are correct, the state could ask to see new policies to fix the problems—but TEA spokeswoman DeEtta Culbertson said it’s too soon to speculate as to what they might be.

“As far as we understand, those numbers are accurate,” Waco ISD’s director of student services, Rick Hartley, told the Observer—though some of the improper expulsions were due to an accounting issue. “Removing a child under 6, there’s no excuse for that. And that principal’s no longer with us.”

Nationwide, it’s well established that African-American students are more likely to face tough discipline at school, but Hartley says Waco ISD hands out discipline evenly, based on the offending behavior, not the student. “We apply the consequence to that behavior. When that happens we don’t look at the ethnicity of the child,” he says. “Our challenge is to prevent the behavior from happening in the first place.”

That focus on early intervention—defusing tension between students and catching signs of bullying early—has become a hallmark of the district’s two-year-old “Suspending Kids to School” program. And Charlene Hamilton, who came from the governor’s office to run the initiative, says their approach is working.

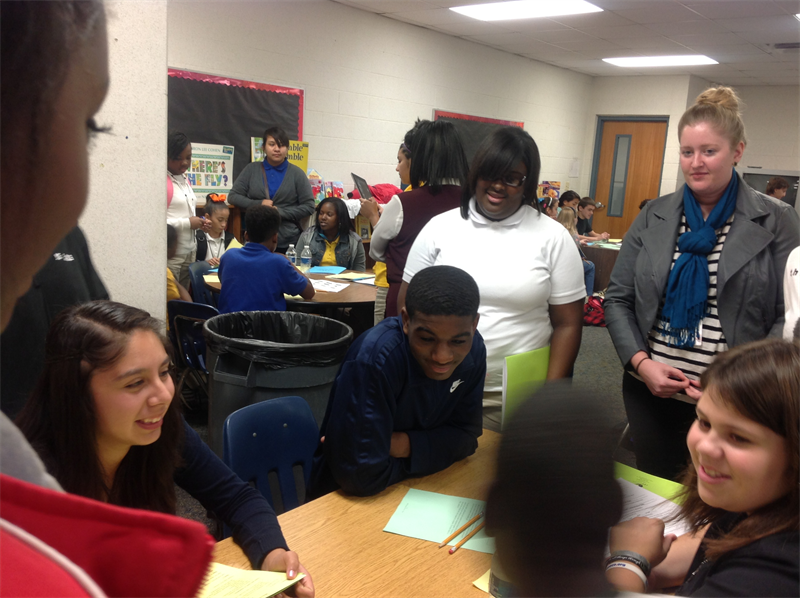

Hamilton trains student “ambassadors” in each high school to watch out for potential problems, and peer mediation and student-run courts to settle scores without school administration getting involved. For students who still seem like they’re headed to an alternative school assignment, Hamilton runs a two-day weekend intervention for students and their parents, which she calls a “very strong diversion tool.”

Every year, more than 100 students have graduated from the Saturday program and avoided disciplinary removal. Around the district, she says, they’re focused on keeping kids in their regular classrooms and reducing alternative school referrals, in-school suspension or expulsion. Which is great, but it doesn’t address the over-representation of black students in those disciplinary decisions.

Though she’d heard about the report from TEA, Hamilton says her program doesn’t see a disproportionate number of African-American students, which may mean principals are just sending more of them straight to alternative school. Though she’s been at it for two years, Hamilton says some administrators need a little more coaxing to change their habits.

“We do really good education here, but we lived in a very punitive culture here in Waco ISD and we’re trying to change that culture,” she says. “We’re constantly, from year to year, educating and re-educating them on what we’re trying to achieve. We’re making headway but it’s baby steps.”