Wall Flowers

Border art projects bloom in the shadow of Trump's wall.

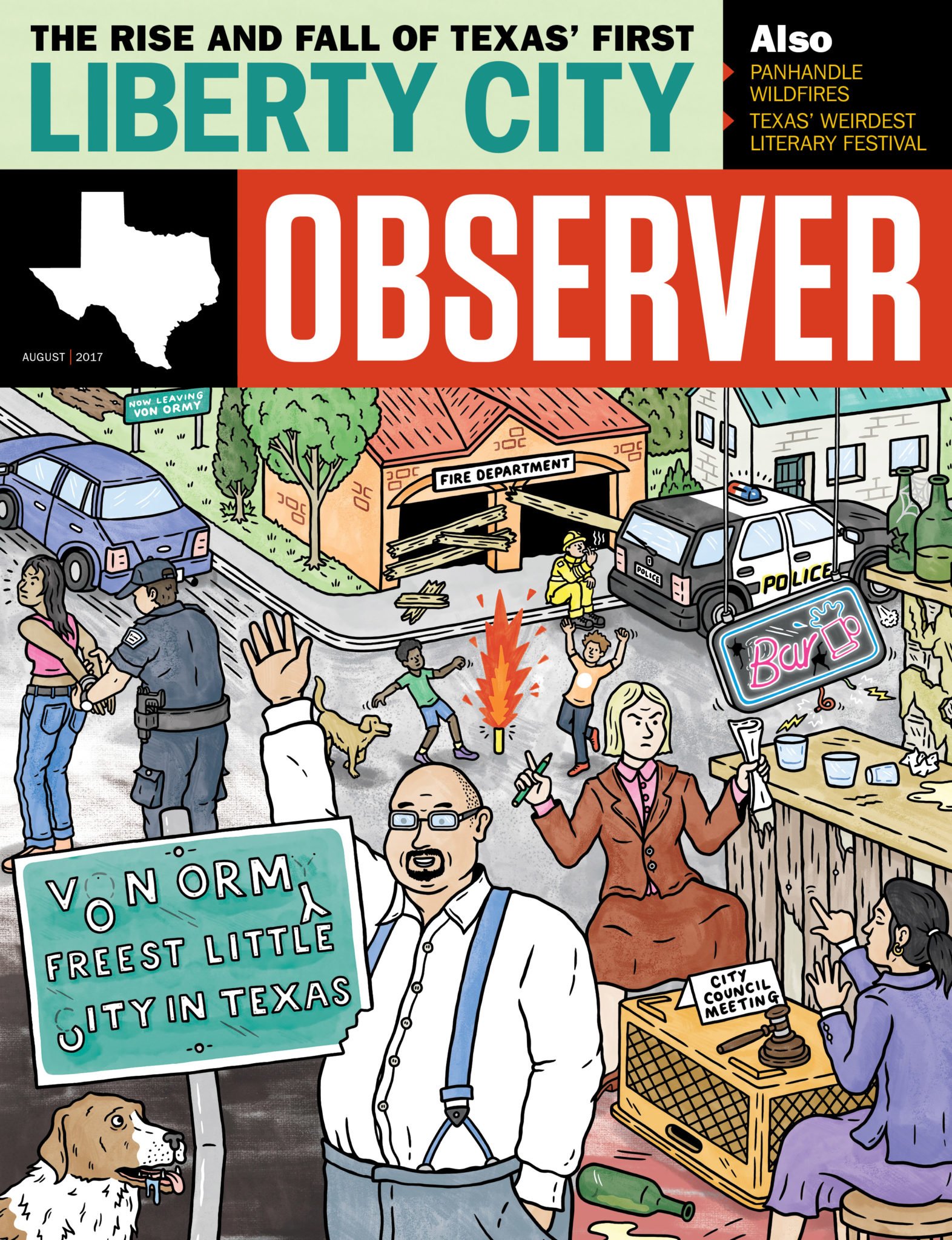

A version of this story ran in the August 2017 issue.

Wall Flowers

Border art projects bloom in the shadow of Trump’s wall.

If you squint hard enough, it’s not difficult to see Donald Trump’s campaign and presidency as a horrifying species of performance art, a virtuoso reality-TV spectacle with all-too-real consequences for the viewers at home. Like good art, Trump’s act is often playful, vivid and hard to pin down; it’s also, like much bad art, devoid of empathy, grace or responsibility for its biases.

Consider the dark conceptual genius that is Trump’s impossible border wall, now legible as a test case of his entire political style. Throughout his 2016 campaign, Trump constantly described his wall-to-be in ludicrous terms — dozens of feet high and growing with every attempt to question its likelihood, financed by some racist neocolonial fever-dream of Mexico, with an imaginary door appearing from time to time. His audacious bluster was dutifully echoed through TV news and social media — repeated first with outrage, then in mild derision and finally absorbed into the zeitgeist. Trump’s wall has already been installed in each of our mental architectures as a symbol of the growing border-security apparatus, a manifestation of the racism and hate laid bare over the past two years or a literal vision of the future of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

Artists have the power to subvert such malicious visions and to offer substitutes. Perhaps the most immediate and striking parody was the release of renderings for a big, beautiful “Prison Wall,” published last year by the Guadalajara architecture firm Estudio 3.14. Taller than a triple-decker sports arena and colored bright pink in homage to the great Mexican designer Luis Barragán, this attempt to translate Trump’s campaign boasts into plans for steel and concrete would stretch nearly 2,000 miles over mountains and deserts, housing a prison large enough to detain 11 million migrants, financed from within by a long chain of indoor maquiladoras. “We believe that this project will allow the general public to literally imagine the gorgeous monstrosity proposed by Mr. Trump,” the creators of the proposal stated on their website.

“It felt like déjà vu. Have people not learned anything from history, that walls do not work?”

So far as alternate visions are concerned, one of the simplest is the petition by famed artist Luis Camnitzer to re-create Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s 1976 installation Running Fence along the entire U.S.-Mexico border. The 24.5-mile-long series of white nylon panels was a seminal work of environmental art in its time. “In full-length today it would transform a racist project into a public art event, and help improve the image of the U.S. with an increasingly needed cultural veneer,” Camnitzer writes.

More than a veneer to cover up Trump’s vulgarity, what the United States most requires is a full-throated cultural response to the wall’s problematic implicit ideologies. What follows are a few projects, from Texas and around the country, that speak truth to power and question the border-security apparatus on its own divided turf.

***

“You Shouldn’t Leave It Gray”

Doerte Weber grew up in divided Germany and has searing memories of driving through heavily policed checkpoints as she traveled through Warsaw Pact territory between West Berlin and the rest of West Germany. More recently, she has lived for years in McAllen, where she and her husband had the habit of driving over to Reynosa for dinner and groceries on a Saturday night. These days, that sort of cross-border lifestyle is much more difficult. “When the whole thing happened with the border wall, it was very upsetting to me, because it felt like déjà vu,” Weber says. “I’ve gone through this. Have people not learned anything from history, that walls do not work?”

This summer at Artpace in San Antonio, Weber is displaying “Checkpoint,” a piece she first installed at the border fence in Brownsville earlier this year. Weber conceived “Checkpoint” as a commentary on both the cautionary European example and the emerging Texas-Mexico experience of border barriers. Using thread and donated plastic newspaper bags, Weber wove 11 tall panels evoking Mexican textile art. Her emphasis on bright color is a tribute to the lively craft traditions of the cultures native to and affected by the border wall, but also a callback to the colorful graffiti that Weber remembers covering the Berlin Wall. “They had not left the gray, they had put color on it, they had left their mark,” she says of the wall of her youth. “That’s a good thing. You shouldn’t leave it gray. That would mean you accept it.”

Weber installed the panels earlier this year directly beside the fence on the grounds of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. She intended it as a very brief, single-day installation, not a public event. Even so, Weber was wary of upsetting the authorities. In fact, she was approached by both a Border Patrol officer and a university security guard. The former, a Minnesotan, complained about the January heat and offered his personal phone number in case anything went wrong. The latter was even friendlier. “He just looked at the weavings and said, ‘My grandmother does this in Mexico,’” Weber says.

To re-create her border installation at Artpace, Weber wove an additional seven panels that depict the border fence as viewed from the original installation site in Brownsville. Weber was particularly pleased that her current installation, which closes August 27, can be seen at all hours of the day through the street-level window of Artpace’s Main Space gallery. She was also happily surprised that several of those who attended her Artpace opening this May shared memories of living near the Berlin Wall and other Iron Curtain barriers. But Weber’s favorite moment of the opening came when the child of an attendee who had introduced herself as an immigrant began exploring and climbing through the hanging panels that represent the Rio Grande Valley fence.

“The fence panels are not sewn together,” Weber explains. “There are openings, because the fence is not whole yet. There are still gaps in it. The little kid just started climbing through it. … I think of all the kids who grow up without knowing the political meaning of the wall, who just cross whenever they can from one country to the next.”

***

“The Wall Is Where We Come From”

To varying degrees, the works in this story all step outside the gallery or museum setting to engage more directly with people and places outside the elite art world. That’s not the only way these artists destabilize traditional ideas of what art is and how it is created. Consider the interest each of these works takes not just in site-specificity, but also ephemerality — the idea that the fullest manifestation of the project’s meaning occurs only during a brief, intense window of time, so that it cannot be fully experienced, let alone bought or sold, by an art patron at a later date. What’s left is the product of that heightened moment: relics, documentation and community-authored material. Intentionally or not, this disorienting effect echoes not just the unsettling no-man’s-land aspect of the contemporary border zone, but also the volatile reality of Trump’s wall, a mirage that is slowly taking on real-world dimensions.

Another fascinating site-specific work with a Texas connection, enacted two years ago but only recently coming to public attention, is the massive installation “Repellent Fence” by the artists Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez and Kade L. Twist, who together call themselves Postcommodity. The trio has made waves this year, with work in the prestigious biennial survey of American art at the Whitney Museum in New York City this spring, another large installation at a New York gallery around the same time, and a new feature-length documentary, Through the Repellent Fence, by Austin director Sam Wainwright Douglas.

“Repellent Fence” represents eight years of collaboration with members of the border communities of Douglas, Arizona, and Agua Prieta, Sonora. The project culminated in a four-day installation, or “ceremony,” in the words of the three artists, who are all indigenous North Americans of diverse heritage. The ceremony was a spectacle in which 28 large, printed balloons were raised in a 2-mile-long stitch pattern along and over the border between the two towns. The artists and their collaborators conceived it as a symbolic “suture,” relinking the divided landscapes and communities.

“We tell stories about where we came from, and for better or worse, the border wall is where we come from.”

Postcommodity chose the area, Twist says, in part because Douglas and Agua Prieta have a legally binding agreement laying out their shared goals. “It was talked about as a sacred document by the community,” Twist says. “For four days and nights, communities came together to embody that document. It was a really powerful, sustained experience.”

The balloons’ design was based on indigenous iconography with a long history on both sides of the border. “The failure of media, thinkers, writers and other artists to recognize people crossing the border as indigenous is very problematic,” says Twist, a member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. “If you look at works we’ve done, they’ve all had the desire to think about the indigeneity of people crossing the border, and the long-term relations that were here before the border existed.”

Douglas, who directed the film about “Repellent Fence,” says that Trump’s racist and vitriolic rhetoric lent urgency to the story he was telling. “It gave the film a lot more weight,” he says. “There needed to be stories to counter that. I think our film became one of those.”

Still, Twist stresses, “Repellent Fence” should not be read primarily in terms of recent headlines, but instead considered as part of a much broader historical narrative. “Our thing is not protest,” Twist says. “We don’t use art as advocacy. We’re storytellers. We tell stories about where we came from, and for better or worse, the border wall is where we come from.”

***

“Spaces to Invite People In”

Rafa Esparza, whose exhibition “Tierra. Sangre. Oro.” (“Earth. Blood. Gold.”) is now open at Ballroom Marfa, is another emerging artist chosen for this year’s Whitney Biennial. Though he works in a variety of media, many of Esparza’s most celebrated recent installations have involved adobe brick-making. While “Repellent Fence” shifted the conventions of classic 1970s land art to include native and community voices and to leave no permanent trace, Esparza puts a different spin on the idea of making art from the landscape — by building structures that are made of earth and will return to earth again.

“I’m not only thinking about adobe as a material that could function as an alternative platform, that could hold objects and create a space for performance or other creative gestures,” says Esparza, whose Whitney installation, a rotunda of adobe bricks decorated with wall hangings, sculptures and sound installations, did just that. “I’m also thinking about where it comes from, its materiality. These bricks are made out of land. When I’m thinking about creating these different spaces, I want to bring in land and our relationship to land as a theme.”

Esparza learned brick-making as an adult from his father, who came to the United States from Durango, Mexico. “Six or seven years ago, we stopped talking for a while,” Esparza says. “I had come out, and he was struggling with accepting that. I asked if he’d teach me how to make these bricks, in order to have a bonding experience with him. He agreed to teach me. We didn’t really have the conversation I was looking for, but it was a first step in mending our relationship.” Since then, Esparza’s father has been involved in all his adobe projects, and he plans to travel to Marfa to help prepare his son’s installation there.

Esparza is cautious about audiences viewing his work as primarily about the border, but he allows that Trump’s wall is an important factor. “The idea of the wall is so present in everyone’s consciousness, because of the moment we’re living in now,” he says. “But when I’m building spaces, they’re really to invite people in, oftentimes people who are excluded or don’t have access to more traditional art spaces.”

***

“To Be Able to Transform Materials, Culture, Politics”

Another commonality linking these projects is engagement with traditional crafts of Mexico and the border region. Esparza’s bricks have an obvious potency in the era of the wall, but textile art is the craft most often used and referenced when making work about the border. It’s easy to see why: The United States and Mexico can feel like two halves of the same fabric, a seam in need of repair.

Margarita Cabrera was born in Monterrey, attended high school in El Paso, went to art school in New York City and returned to El Paso to develop her adult art practice. Her most resonant project for the border-wall era is “Space In Between,” a series of sewing and embroidery workshops aimed at immigrant communities. In the course of the workshops, using Border Patrol uniforms as material, Cabrera and her collaborators create sewn sculptures of cacti and other desert flora. The workshop participants are also instructed in a traditional embroidery technique from the Otomi people of the Mexican state of Hidalgo, which they use to inscribe elements of their own border-crossing stories on the altered uniforms.

“It’s an object that symbolizes specific things for one group of people and different things for other groups,” Cabrera says of the Border Patrol outfits. “For instance, you’ve got people who look at the uniform, who see something that represents safety, security, control. Then you’ve got other groups that look at the uniform and immediately have a sense of fear … of something that can be dangerous, that can represent death for them.”

Cabrera’s first “Space In Between” workshop was at Houston’s BOX 13 ArtSpace in 2010. Since then, she’s hosted several more in cities all around the United States, including in Phoenix last fall. She hopes eventually to be able to display all the works together in a sort of desert garden of border-crossing narratives.

Those wishing to see or be involved in one of Cabrera’s workshops can take part in a somewhat similar project she’s running this summer in San Antonio called “Árbol de la Vida,” or “Tree of Life.” For this project, Cabrera invited San Antonio residents to a series of charlas, storytelling workshops where she collected stories about the city’s ranching and mission history. This summer, the narratives are being translated into clay and fired into lasting sculptures. The sculptures will be hung from a metal “tree” near the Mission San Francisco de la Espada, where they will mingle to tell a public-art story of the city’s culturally diverse origins. As always, Cabrera’s medium is part of the message. The ceramic process used for “Árbol de la Vida” dates back to the ancient Olmecs of the Mexican Gulf Coast.

Cabrera uses traditional craft styles as a means of synthesis, bringing people together to change the conversation about border-crossers. “One thing that keeps me thinking is this anti-immigrant rhetoric, this negative approach to our international community,” Cabrera says. “Focusing on art processes that celebrate the amazing characteristics and qualities of our immigrants, we shed light on our community as powerful people. … To be able to transform materials, ways of thinking and being, transform culture, transform politics — for me, that’s a part of the process I like to be involved with.”

It’s a heady thought, the idea that an artist could transform the fabric of our culture and our politics as straightforwardly as she reshapes the fabric of a police uniform. But our experience tells us that it is possible. We are in the unfortunate position of having the biggest bully pulpit in the world occupied by a bully — a man eager to build up negative stereotypes of minorities and outsiders as well as his fantasy fortifications against both. We know from our own inability to fully disbelieve in the Trump wall that his rhetoric has had its intended effect. The antidote is art: different ways of looking at the world, manifested in deep, coherent exercises of empathy and solidarity, experiences that we can step into and share. That’s what these artists are building here in Texas. We can only hope their visions rise up faster than the wall.

This article first appears in the August 2017 issue of the Texas Observer. Read more from the issue or become a member now to see our reporting before it’s published online.