Rural East Texas has some of the highest suicide rates in the state. But the safety net for people who need help is being stretched thin, and some Texans are falling through.

by Christopher Collins

May 29, 2019

I.

The mind of Keilan Banks is perpetually caught between two worlds. In one of them — what many of us would call the “real world” — he attends art school at a community college in Kilgore, a small town just southwest of Longview in East Texas. He works at a local Walmart four days a week wrangling shopping carts. The other world is one that Keilan alone can see: a frightening, shadowy place where faceless figures manifest and winged devils circle overhead. Disembodied voices sound from all directions, Keilan says, urging him to hurt himself.

Every so often the two worlds collide. And when they do, it can be explosive.

One morning last year, in late June, Keilan drove from his home in west Longview to a nearby trailer park where his aunt and uncle live; they don’t have a vehicle and had asked Keilan for a ride to run a few errands. Keilan had woken up in a foul mood that morning, so he wasn’t talking much as they traveled on McCann Road, a main thoroughfare that traverses the town’s northern half. His aunt, Catharina Jones, asked why he was giving them the silent treatment. Had they interrupted him? “I wasn’t busy doing nothin’,” Keilan responded. “I was just thinking about killing myself.”

He threw open the vehicle’s center console, reached inside and produced a knife, brandishing it as he punched the gas. “Gimme the knife!” Keilan’s uncle, Michael James White, shouted from the passenger seat. But Keilan held on to the weapon and kept driving.

From the backseat, Catharina managed to soothe her nephew. She doesn’t remember what she said, exactly, but it was enough to get him to stop the car and put down the knife. Michael snatched it away when he had the chance. Crisis averted, Keilan drove Michael and Catharina back to their trailer. He called his mom to tell her what happened and she drove him to the emergency room at CHRISTUS Good Shepherd Medical Center. Later that day he was taken to the Northeast Texas Regional Crisis Response Center in Atlanta, an inpatient mental health center an hour away in Texas’ far northeastern corner.

Keilan was already familiar with the facility. It was the same place he’d been sent less than a month earlier, a few weeks before his 21st birthday, when he made his first suicide attempt. In that incident, while working at Walmart, Keilan cut his arm repeatedly with a knife. He told a store manager what happened, showing him the injury, and the manager suggested Keilan go to the hospital. Another stint in the Good Shepherd emergency room. Another trip to the crisis center.

“[The voices] were telling me I was worthless. They were telling me I had to end it all,” said Keilan, who has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and severe anxiety, and some days is so wracked by depression that he can barely get out of bed. “I was just so confused and they just kept pressuring me. … I just wanted it to stop.”

The pocket of East Texas that Keilan calls home is among the state’s regions hit hardest by suicide. The most recent federal data show that in Gregg County, which includes Longview, 335 people died by suicide from 1999 to 2017. The county had a suicide rate of 15 deaths per 100,000 people in that time period, compared to the average state rate of 11.4. Several nearby, more rural counties — including Marion and Morris counties, just north of Gregg — have even higher suicide rates.

No one knows for sure why this part of East Texas is especially susceptible to suicide, in part because the causes of suicide are complex, but also because virtually no one is studying the growing problem. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide rates in Texas have been climbing since 2000, when the rate was 10.2 per 100,000 people. By 2017, the rate had risen to 13.4. A handful of community activists, along with cash-strapped local mental health authorities, are trying to address the complex web of social, economic and health problems behind suicide. But they’re doing so without much outside help. Despite increasing recognition of rising suicide rates as an urgent public health problem, the state of Texas isn’t spending any money to investigate the roots of the crisis in rural Texas, much less taking action to find remedies.

Kathleen Belanger, a professor emeritus of social work at Stephen F. Austin University in Nacogdoches, is one of the few experts who has studied why suicide rates are higher in East Texas than in other rural regions. She said the plight faced by the region is likely a result of sputtering rural economies, a paucity of social services such as foster care, and a threadbare health care system. “Suicide is just one more piece of this puzzle,” Belanger said. “I think the state and the country have not devoted the necessary resources.”

The Texas Observer spent more than a year examining the problem of suicide in East Texas, interviewing survivors of suicide attempts, the families of those who have died by suicide, mental health professionals, community advocates and others. The investigation found that as suicide has quietly gripped many communities here, the state’s mental health care system is being stretched well past its limit. The relatively few psychiatrists who choose to work in East Texas have months-long waiting lists and sometimes opt not to treat the uninsured. Until the Observer began asking questions, the state health agency charged with addressing the problem had repeatedly failed to meet basic responsibilities laid out by the Legislature, such as updating a statewide suicide action plan and creating local protocols to prevent suicide.

“The mental health system is so broken,” said Mildred Witte, who runs the Tyler chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), where Keilan attends monthly meetings. “It’s a problem pile-up … you hardly know where to begin.” She identified a dearth of available beds in Texas’ 10 state-run psychiatric hospitals, along with the Legislature’s apparent unwillingness to fully fund mental health services, as the biggest problems. For Keilan, who hasn’t had health insurance since he was a child, it was difficult to get mental health services, he says. And though he has been sent to an inpatient mental health facility twice in the last year, Keilan was booted out after only a few days — hardly enough time for real healing to occur.

In April, Keilan was struggling to stay alive. His mental state can careen from deep depression to frenzied mania. On the worst days, the voices — unfamiliar men and women who scream, plead or whisper — grow louder than usual, sometimes urging him to kill himself. The “visions” scare him, too: Once, he saw himself standing by a curb when some “unseen force” pushed him into oncoming traffic. “It’s like, if we had an off switch, we would turn it off, but it’s gonna make you see it, no matter what kind of mood you’re in,” he said.

Keilan attempted suicide a third time on December 18, about a week before we talked for the first time. He tried to overdose on his antipsychotic medication at his home; he survived and slept for the rest of the day. “There are times I wish it had worked,” he said. In that way, the attempt was like others I encountered in my reporting: a desperate act in a quiet place, undertaken with no fanfare or intervention, when a person has just lost hope.

II.

Carol Dubose was in the Fort Worth suburb of Crowley visiting her newborn nephew on January 15, 2018, when she got word of a monster ice storm moving through the state. She decided to book it back to her East Texas home of Daingerfield, a rural town of 2,400 in Morris County, an hour north of Longview, before the roads slicked over.

The rain was turning to sleet in the early evening when Carol and her husband, James Dubose, started shooting whiskey and fighting at their home, a gutted gas station on the west side of town that Carol’s mother shuttered in the early 1980s after the nearby Lone Star Steel plant laid off thousands of workers.

“When we argued it was bad and it was loud. Not physical, but loud and bad,” Carol said. Suddenly, James, who had been watching a hockey game in the living room, burst through their bedroom doorway wielding two shotguns. “I’ve had enough. I just can’t take it anymore,” he said.

Then he walked outside. It was the last time Carol would see him alive.

“I was talking to my friend [on the phone] and I heard the shotgun go off,” Carol said. “I said, ‘OK, he just wants me to get off the phone and come outside. I gotta go.”

Carol got up and opened the front door to find James slumped over in his favorite chair. One of the home’s two massive glass windows was shattered. Carol called the sheriff’s office first, then her relatives in Crowley. They got to Daingerfield as quickly as they could, skidding over ice-slicked roads.

What happened next demonstrates how many officials still treat suicide as a private affair, rather than a public health issue. Shortly after the death, a local official, Justice of the Peace Nikita Fridia, launched an investigation into James’ death. Such “inquest” investigations are required by state law, but they are often perfunctory.

Texas state law requires that either a medical examiner or a justice of the peace investigate “unattended” deaths — basically, deaths that occur outside of a hospital. Only the 13 most-populous counties in Texas have medical examiners, physicians who are specially trained to investigate how a person died. In the other 241 counties, including Morris and Gregg counties, the job falls to JPs, elected officials whose duties also include trying truancy cases, officiating marriages and overseeing evictions. Even though JPs rarely have medical training, state law gives them enormous leeway in investigating deaths. JPs can use whatever information they want to figure out how someone died, such as witness statements and medical records, but nothing requires them to review potentially important evidence, visit the scene of a death or request an autopsy, which could reveal valuable clues into the circumstances of a death.

Fridia was the coroner called to the Dubose house that cold January morning. After a quick assessment of the scene and a chat with the cops who responded to the 911 call, she determined the death a suicide. If Fridia had asked, Carol could have told her that James had descended into depression after a string of personal tragedies. He lost part of his ear to a dog attack, and then, after he retired, he realized he didn’t have enough income to afford his antidepressants. But Fridia didn’t inquire about any of that, despite the fact that mental health professionals say comprehensive investigations into suicides can inform prevention efforts and find important connections between other regionally clustered self-inflicted deaths.

It was the second suicide Fridia had worked in two months, she said. In a span of less than a year, Morris County saw four suicide deaths, about double its annual average.

Fridia says she doesn’t know why suicides are stacking up in her caseload. She doesn’t interview family members, friends or witnesses to ascertain why a person has taken their own life. She doesn’t try to find common threads in the deaths that could give insight into the root causes. “It’s not anything I ask,” she said. Once a death has been determined a suicide, Fridia’s probe all but ceases.

Jennifer Easley, the county’s other justice of the peace, also tends to not ask many questions when investigating deaths by suicide. “We’re not thinking, ‘Why’d you do this?’” she said. If a death is ruled a suicide, “That’s usually where our part ends. We don’t go into the whole ‘Why, was he employed, did he break up with his girlfriend, that kind of thing,” Easley said.

It’s simply not their job to figure out why a person has taken their own life, or if there’s a larger pattern to suicides in Morris County. Turns out it’s not anyone else’s job, either.

“[JPs] would never be like, ‘Why do you think this happened?’ They’re not there to dig into people’s personal lives,” said Thea Whalen, executive director of the Texas Justice Court Training Center, an organization tasked with providing continuing education to the states’ justices of the peace. “These are their friends and people they know. … They are trying to do the best job they can.”

The local sheriff’s office is also in the dark about why the county has such a high suicide rate, even though deputies frequently respond to the incidents and conduct interviews with witnesses while the cause of death is still unknown. “I really don’t know why, to be honest with you,” said Jack Martin, the county sheriff.

More comprehensive postmortem investigations could shed light not just on individual suicides, but also on trends driving the deaths in East Texas. According to the American Association of Suicidology, structured inquiries called psychological autopsies are a “best practice postmortem procedure” for finding connections between suicide cases and informing prevention efforts. The autopsies include reviewing police reports and medical files, along with interviewing family members and friends to sort out why a person has died, said Bart Andrews, a psychologist who sits on the association’s board of directors. “They’re important, useful tools,” said Andrews. “All of those suicides [in Morris County] should be getting psychological autopsies.”

It’s possible that some common threads connect the deaths in Morris County, even given the office’s cursory information-gathering. But when I asked to review case files for the 12 suicides that have been documented here since 2012, officials could find only five.

When I visited the office again in March, Easley said the records still hadn’t been located. She admitted that misplacing such important documents was a problem. “You ought to be able to find stuff like that. If those physical files are gone or destroyed … where would you go to find that information?” Easley said. “It’d be gone.”

Andrews said that Morris County’s hasty death investigations and shoddy recordkeeping are disappointing. “They’re not taking the suicides seriously,” he said. “You can tell that these suicides aren’t getting any significant attention by the quality of the records they keep.”

For the last four years, the state has been slow to act on its own official suicide prevention plan. In some cases, it has failed to follow recommendations at all. First drafted in 2001, the plan is a list of strategies and guidelines blessed by the governor, the state health agency and the Legislature almost two decades ago. “Suicide is considered to be among one of the most preventable of public health tragedies,” the preface of the 2014 version reads. But it seemed to have been all but forgotten — at least until the Observer sent dozens of questions to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission over the course of five months. Though the plan recommended that the Texas Department of State Health Services create comprehensive suicide prevention protocols for local mental health authorities by 2017, the agency didn’t start finalizing the project until mid-2018. DSHS had also failed to hold an annual statewide suicide prevention symposium and two regional events, per the plan, in 2017 and 2018.

Even with DSHS’ newfound interest in the state plan, there’s still plenty of work that’s not being done. For example, the plan also recommended that DSHS establish an internal “injury and violence prevention branch” to ramp up suicide prevention services at the agency; the branch was created, but its suicide prevention work is currently limited to a single pilot project in Comal County. The plan also suggests that it be reviewed to determine if it’s actually helping to prevent suicides in Texas. The review hasn’t occurred.

Christine Mann, a health commission spokesperson, said the failure to follow some of the plan’s recommendations is a result of federal grant money drying up, along with limitations placed on previous grants. She added that Mental Health America, an organization that once acted as the Texas Suicide Prevention Council’s underwriter, “disbanded” in 2016 and stopped funding the council. State legislators haven’t stepped up to fill the gaps left by dwindling federal grants — Texas ranks next to last in mental health spending per capita in the nation.

Meanwhile, those whose lives have been touched by suicide must find a way to keep living. James and Carol’s adult grandson, who was devastated by his grandfather’s death, has attempted suicide at least twice, and said he’s struggled to find adequate mental health resources in rural East Texas. “That was basically my father figure,” said the grandson, whom the Observer chose not to name in this article. “I made some mistakes, but he continued to help me out and still loved me. When I lost him, I was like, ‘Not you too, grandpa.’”

Carol herself tried to take her own life four years ago by swallowing a handful of sleeping pills. In January and February 2018, after James’ death, Carol drank “pretty much nonstop,” she said. One night, Carol was driving drunk when she was pulled over by a highway patrolman. She was arrested and taken to jail for the first time in her life.

Now Carol is trying to put her life back together. She’s been going through piles of old things in the house, reading the love letters James wrote her. Carol said the process has been painful but also cathartic. Through a local community health center, she’s gotten access to a therapist and antidepressants. Carol still lives in the house where James died. The shattered window is still boarded up.

III.

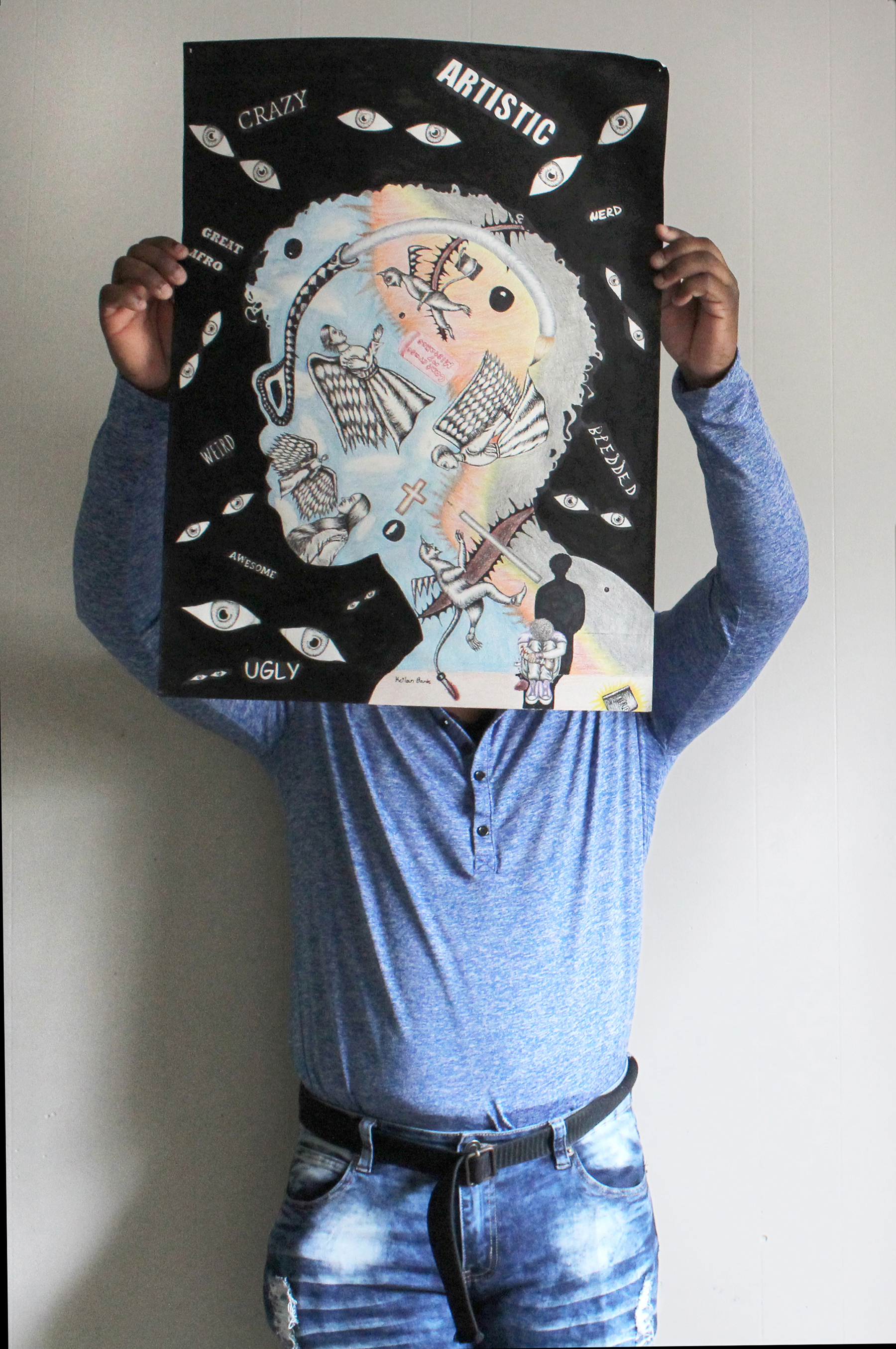

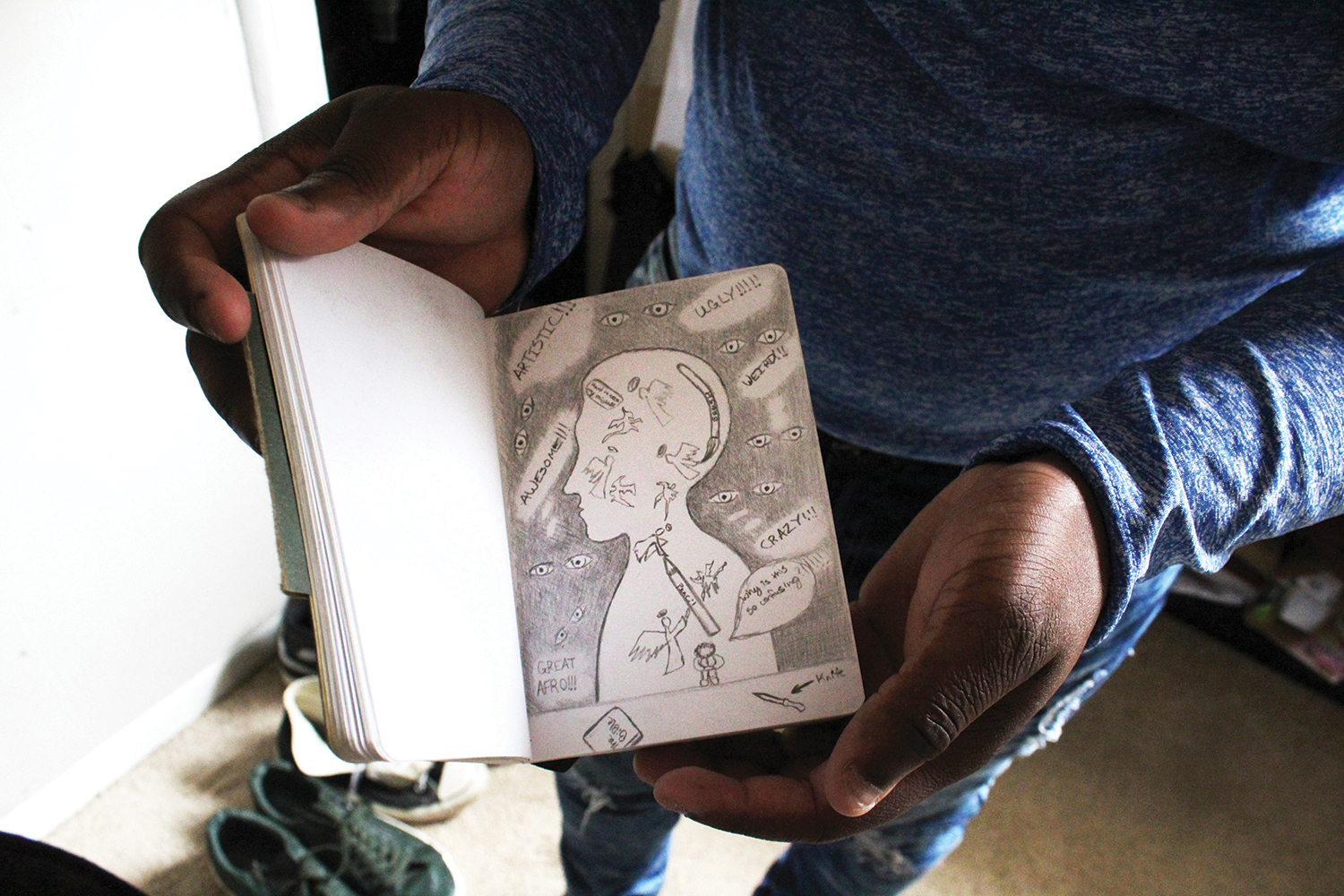

One day in January, Keilan lugged three long, slim cases from his bedroom closet into the living room: his art portfolio. He unzipped them and began pulling out a stack of drawings. One of them was striking: It was an image of the inside of Keilan’s head, where winged angels encounter knife-tailed demons. In one corner of his mind, a miniature Keilan sits with his head cradled on his knees as a shadow looms just behind. Floating above his head, on the drawing’s black background, wild eyes peer out at the viewer, and the words, “WEIRD,” “BLESSED,” “CRAZY,” and “GREAT AFRO” materialize.

Keilan wants to be a professional artist some day, to have his own gallery opening, but those dreams aren’t likely in the short term. After he gets his associate’s degree this summer, he plans to shelve his college career and go to work full-time at Walmart. One of the chief reasons is to get health insurance.

Keilan said he knew virtually nothing about mental illness until he had almost graduated from high school, when a friend who had noticed his extreme mood changes asked Keilan if he was bipolar. “I don’t even know what that is,” he told the friend. He figured hearing voices and seeing visions was normal. Keilan’s mental illness ramped up in 2017, when his friend was killed in a car wreck. “The voices were showing up more and more. They just kept coming. It got to the point to where, I need some help,” he said.

But when Keilan began calling private psychiatrists in Longview for an appointment, his efforts were stymied. “They always ask if you have insurance,” he said. “Thing was, in spite of my having a job and everything, I didn’t have enough [money] for insurance.” After a month of calling around, he went to his college counselor, who referred him to the Samaritan Counseling Center of East Texas, a private organization in Kilgore. A therapist there recommended that Keilan contact Community Healthcore, one of 39 local mental health authorities scattered across the state.

Keilan said he was surprised that he had to wait about a month to start getting help at Community Healthcore. As his mental health was deteriorating in late 2017, Keilan was told he’d be put at the end of a long waitlist for psychiatry and other services. “It’s just gonna take a while. I had to tell them that I’m feeling bad about myself, I keep hearing these voices constantly. I had to wait,” he said. Other people interviewed for this story, including Keilan’s aunt and uncle, who said they are mentally ill, also reported long wait times to access services from the health authority.

After waiting about a month, in late 2017 or early 2018 Keilan got services from Community Healthcore: He now has occasional access to a psychiatrist — though he sometimes must wait two months for an appointment — and gets most of the five prescription medications he takes for free.

By early 2018, Keilan had taken advantage of almost all the services available to an uninsured, mentally ill young man in East Texas: He was speaking to a counselor weekly, attending monthly group therapy sessions at NAMI and had linked up with the local mental health authority. But without health insurance, he couldn’t access additional services that might have helped stave off the creeping thoughts of self-harm. And when he was shuffled from Good Shepherd to the crisis center an hour away in Atlanta twice in one month, he got a crash course in how thin the safety net is for suicidal people in East Texas.

After Keilan’s first suicide attempt — when he cut his arm at Walmart — his mother took him to the hospital ER. Though emergency rooms are ill-suited for treating suicidal patients, it’s where many of them end up because there’s virtually nowhere else to go, said Terry Scoggin, CEO of Titus Regional Medical Center in Mount Pleasant. The best that hospital staff can do is put in a request to have the patient sent to a state mental hospital, facilities that tend to stay booked due to overwhelming regional demand. Scoggin said that the number of spots available to the general population is so miniscule that patients sometimes must wait days in the ER for a mental health bed to open up.

Keilan estimates he was kept at Good Shepherd for about eight hours before being sent to the crisis center, which may have taken so long because he refused to go willingly. An “emergency detention warrant” was issued by a county official to have Keilan involuntarily committed to the Atlanta facility. He stayed there for only two days before being released. At the time, Keilan was happy they let him go so quickly, he said; he could sleep for only a couple of hours at a time in the room he shared with another patient, and his heart wouldn’t stop racing. A follow-up appointment at Community Healthcore was scheduled for two days after his release.

Apparently the intervention didn’t take. Keilan’s next suicide attempt, when he pulled out a knife while speeding through Longview, led him once again to the Good Shepherd emergency room before being transferred to the crisis center in Atlanta. This time, he was discharged after four days, though he still felt suicidal at the time of his release, he said. Inside a transport van headed back to Longview, Keilan saw a vision of himself opening the back door of the van and launching himself out onto the pavement. He had started to reach for the door handle but thought better of it.

Looking back on the hospitalizations, Keilan thinks he would have benefited from more time at the facility. “I think I probably should have stayed longer,” he said. “If I’d have stayed, things may have been better.”

In a 2018 interview, Rick Roberts, the organization’s director of programs, said Community Healthcore could provide better services if it had a bigger budget. “We try to keep a wide variety of things we can do, but you have to balance that with the ability to keep those things afloat. Funding and staffing are always issues,” he said.

“Right now, trying to find long-term treatment for anyone in a psychiatric facility is almost impossible,” said Paula Lundberg-Love, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Tyler and a licensed professional counselor. There are some private options available, such as Christian boarding schools and tough-love camps, she said, but you’ve got to shell out $50,000 to $60,000, an impossible hurdle even for some of the area’s middle-class residents.

Dr. David Lakey, former commissioner of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, told the Observer that the state needs to “rethink” its mental health treatment system. “A lot of times people get discharged from the hospital and straight into the community and don’t have that support there. Or they don’t have a safe place to be and they get readmitted,” he said.

“The current mental health system is ineffective because of the structural design,” he added.

The crisis center itself is a response to an issue state health officials have struggled to address for years: the extremely limited space in the network of state-run psychiatric hospitals. Two of those facilities, the aging Rusk and Terrell state hospitals, are in East Texas and in need of major repairs. Though the state has roughly 2,900 psychiatric beds at Rusk, Terrell and eight other facilities, many of those are occupied by “forensic cases,” patients referred to a state hospital by the criminal justice system after being deemed incompetent to stand trial or not guilty by reason of insanity. It’s slim pickings for people like Keilan, who need immediate mental health treatment but haven’t committed a crime. “The demand is there,” Roberts said. “State hospitals are filled with forensic beds, so it does get pushed back to the communities. It’s certainly a challenge.”

In 2014, it appeared as if the mental health care landscape in this part of East Texas would improve at least marginally. Community Healthcore leveraged federal funding to construct the 25-bed mental health crisis center in Atlanta, where patients who presented to local ERs could get psychiatric treatment without having to wait for a spot at a state psychiatric hospital. At that time, Community Healthcore also operated two other crisis centers in Kilgore and Marshall. But the organization opted to close the 16-bed Marshall location early last year after plumbing issues rendered it uninhabitable. Also last year, the health authority closed the nine-bed facility in Kilgore, too, folding it into the Atlanta location. Now, Community Healthcore is considering paring the Atlanta center’s capacity down to 14 beds — a reduction of almost half — to provide “a higher level of care” at the facility, though a deal with the state to maintain current capacity is also being considered.

To make matters worse, the funding mechanism used by Community Healthcore to partially fund the Atlanta facility is likely to disappear. The center was created through the Section 1115 Medicaid waiver, a program that pays Texas health care providers to implement innovative solutions to local needs. Community Healthcore has utilized one portion of the waiver to bolster local access to mental health crisis care.

But funding for the waiver program, which has helped pay for hundreds of mental health projects in Texas, is set to be stepped down in one year and eliminated in three. Waiver money accounts for one-third of the funds used by community mental health centers to treat the mentally ill and the developmentally disabled, according to a Houston Chronicle op-ed written by four leaders of prominent Texas health care provider associations. Loss of the funding could cause “devastation” to mental health services, they wrote — approximately 173,000 people benefitted from those services in 2017.

IV.

April 17, 2018, was a whirlwind day for Martha Baker, a former Daingerfield school nurse who, despite being a 68-year-old retiree, seems to stay busier than just about anyone else in Morris County. Baker is the leader of a ragtag community group called Ounce of Prevention. The loose coalition of health care professionals, substance abuse advocates, religious leaders, businesspeople and others is Morris County’s attempt to address the myriad problems that fuel suicide.

At 11 a.m. that day, Baker, who wears her gray hair short and sports glimmering gold earrings and necklaces, convened the group’s regular monthly meeting. “It is unacceptable that we have high rates of suicide, that we have high rates of anything. So work with us,” Baker said before introducing the speakers: a director at Community Healthcore who briefed attendees on a program for at-risk youth; a Child Protective Services employee trying to recruit foster families in Morris County; and a child abuse prevention advocate passing out pamphlets.

When the meeting wrapped up at noon, Baker zipped across the street to Fran’s Barbecue and Pizza to talk about suicide with two Daingerfield school counselors and Linda White, a retired Longview emergency room nurse who once tried to kill herself by parking her car on a railroad track. The train stopped just in time, she said. White, a recovered alcoholic, now leads substance abuse classes in the back building of a Daingerfield church, which keeps her “busier than a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs,” she said.

That evening, Ounce of Prevention members, along with representatives of state and local government, county residents and others, packed Daingerfield High School for a town hall meeting to discuss a project that could pave the way to Morris County’s revitalization. Inside the school’s auditorium, Shannon Cox-Kelley, the dean of health sciences at Northeast Texas Community College in Mount Pleasant, walked an audience of 100 people through a PowerPoint presentation on why, as one slide put it, “East Texas is the new South Texas.”

Despite being 600 miles apart, the Rio Grande Valley and Morris County suffer from similar health problems: high uninsured rates, elevated poverty levels and widespread chronic disease. Cox-Kelley says the comparison is important — it’s a way to show that the problems faced by the county’s residents are surmountable. “When I started studying community health, the big focus in Texas was South Texas. They had the worst health rates in the state. What happened as a result of that is that a lot of funding went that way. A lot of initiatives were born. … South Texas is becoming much healthier,” she said.

Morris County could soon take its first steps along that same path. Last year, Cox-Kelley secured a $400,000 grant from the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health to improve Morris County’s dismal health outcomes, including suicide. It’s enough money to develop a comprehensive plan and to leverage the remaining dollars as a match for future grant funding.

“We’re going to have to take baby steps if we’re going to grow. But we can make big things happen,” she said. She stressed that in order to reverse Morris County’s decline, the community will have to be engaged, and that it will take the support of “everyone in this building.”

Mildred Witte, who runs the Tyler chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, is also working to ease the suicide crisis in East Texas. Her group recently started biweekly “connection” support meetings, which Keilan attends, for suicidal and mentally ill people.

“I love the connection group,” she said. “It’s something social. You feel very alone when your mind has deserted you. When they realize there are others, they don’t feel so alone.” Since October, eight mentally ill people have undergone training to act as peer facilitators of the group sessions — the plan is to dispatch them to other towns in the region.

In Longview, advocates are working to resurrect the NAMI chapter that folded five years ago, which would greatly reduce Keilan’s current 45-minute travel time to Tyler for meetings. On March 25, they held a meeting in Longview to elect a board of directors, the first step in getting services restarted. Like Martha Baker and other advocates in Morris County, NAMI’s Tyler chapter has scrambled for funding. The group has an annual budget of roughly $25,000; it can’t afford a director, which is why Witte works on a volunteer basis.

Keilan has begun exploring a new art form — writing — to quiet the voices in his head. He’s started a novel titled Relapse of the Mind, wherein a young woman battles mental illness and a bevy of other challenges in an attempt to live a “normal” life. He’s got the first chapter completed, he said, and will keep plugging away at it when he has the energy to do so. Keilan said the book will carry an inspirational message for readers who struggle with mental illness and suicidal thoughts, but the message could very well double as a piece of advice to himself: “It’s gonna let you know that even if you’re going through this, it’s gonna get better,” Keilan said. “You’re gonna get out of it.”

Another piece of advice, which Keilan has a habit of sprinkling throughout our conversations, is that suicidal people can find their own ways to cope with thoughts of self-harm, whether with exercise, cooking or drawing pictures. Aside from making art, Keilan’s preferred coping mechanism is jamming to classic rock. He’s a big fan of Fleetwood Mac; his favorite song is “Rhiannon.” The song’s chorus poses an apt question for Keilan and countless others in his position: Will you ever win?

Keilan wants more than anything for the answer to be “yes.”

Illustration by Michael Hirshon.