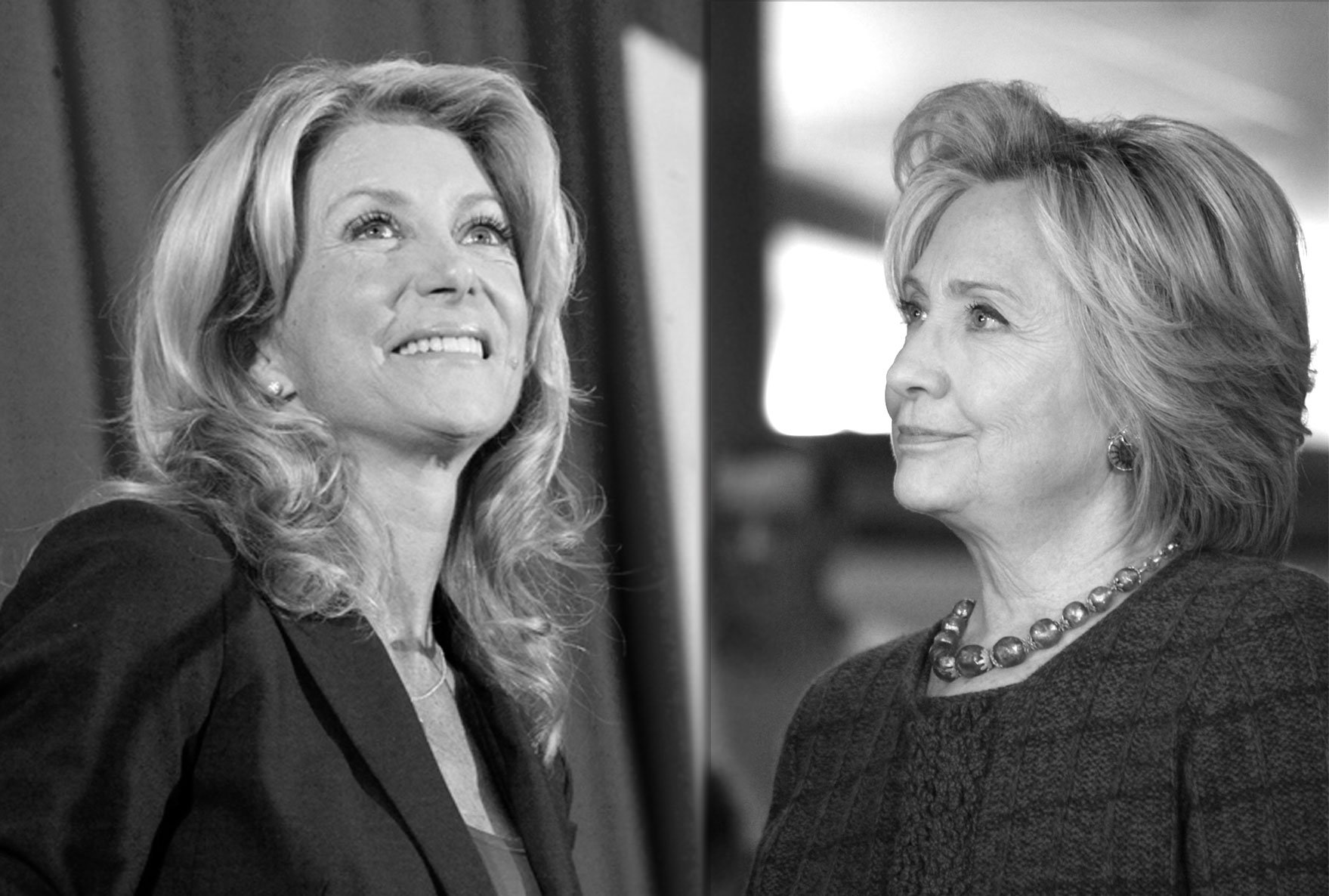

What Wendy Davis Can Teach Texas About Hillary Clinton

White Texans didn't turn up for Davis in 2014. Can Donald Trump alienate enough of them to make Clinton competitive?

They called her a crook, even though official investigations turned up no wrongdoing. They called her corrupt, even as she worked across the aisle to find common ground with political opponents. And, of course, they questioned her morals and dedication as a mother and a wife, calling her absent, ungrateful, even gold-digging. And she wasn’t agreeable enough. She was too cold, too wonky, unable to connect with voters.

That’s how they talked about Wendy Davis during her gubernatorial run back in 2014. That’s how they’re talking about Hillary Clinton now. They’ll probably still be talking about Clinton like this by the time she definitively wipes the floor with Donald Trump’s bad coiffure on the night of November 8.

Whether Texas will be a string in that poorly styled mop is another question. Much was made of the astonishing polls that showed Clinton and Trump within single digits of each other here. Certainly Donald Trump’s bigoted rhetoric and enthusiasm for a border wall has made him deeply unfavorable with voters of color, especially Latinx voters, who Republicans have tried to court for decades. And the way he talks about women — approximately half of whom are not white — has disgusted them (and even some of the guys we know).

Surely, surely, Trump has crossed some vital line with the not-white-dude voters of the world that’ll change this here landscape forever. Right?

Amid the hopeful hand-wringing about Clinton closing the gap, I can’t help but think of Davis’ crushing loss to Greg Abbott — especially among white voters and particularly among white women, who Davis actively courted. Back in 2014, my post-election take was pretty simple: White women need to get our shit together if we’re going to stop shoring up a Republican establishment that fails to stand with women, and our families, at every opportunity. I described, broadly, what I think of as a crisis of empathy in the white community, a widespread refusal to vote for anything but the status quo.

Is it possible that Donald Trump, unintelligible on social issues and unable to detail even the basics of a presidential platform, will manage to alienate enough moderate conservative white ladies (and the men who purport to love them) that they’ll either stay home or — the mind boggles — turn out for Clinton? Can white voters’ myopia about the greater good be overcome not just by Trump’s unparalleled unfitness for office, but by the Trump-fueled realization that the Republican Party is a hot mess for standing behind him?

I couldn’t decide how I felt about the answer to these questions, knowing as I do that Texas voters who look like me simply don’t tend to favor Democrats of any gender. So I asked Davis herself.

“It’s not that Hillary has completely broken through with women,” she told me, “but [Trump’s] turned off enough women that he’s not going to perform with them at the level that he ought to perform.”

Pair that with Trump’s unrestrained racial bigotry, and it’s “the perfect storm,” she said. “A candidate that Latinos love and a candidate that Latinos revile, going against each other.”

Looking at Davis’ 2014 bid may give us a window into whether Hillary Clinton can capture those voters who didn’t show up for her, and enough of them to make Texas even close to competitive this year.

White women need to get our shit together if we’re going to stop shoring up a Republican establishment that fails to stand with women, and our families, at every opportunity.

“When I was asked [the] question during my race, ‘Do you feel like you’re being treated differently as a woman candidate?’” she said, “I always dodged that question.”

She didn’t want to be seen as weak, a complainer. “I would just say no,” she told me, even “when in my mind, of course, in my mind I knew I was being treated differently, but I didn’t want to sound like a whiner.”

But Clinton has turned attacks on her gender into pro-Hillary campaign swag like the official Hillary “woman card.” When Donald Trump hissed his third-debate insult, “Such a nasty woman,” it took only hours for “nasty woman” T-shirts, mugs and stickers to surface online. Senator Elizabeth Warren quickly called on “nasty women” to descend upon the polls at a Clinton campaign stop.

Davis said she wished she’d have done something similar in her campaign. “One of the things I’d do differently is I would say, ‘Yes, it is happening,” she said. “Because I think when we name it, we create a climate where we can shame it. And we create an environment where there can be a consequence to it.”

But it can be particularly difficult to name and shame gender-based opposition to women holding office when it’s more about subtext than, say, rattling off a bunch of hooey about menstruation or questioning whether we’re hot enough to sexually assault.

Both Clinton and Davis have been criticized for their private marital decisions — Davis for leaving her husband, and Clinton for staying with hers. What might sound, on the surface, like questions about character or reliability are, at heart, about our most fundamental conceptions of womanhood, wifehood and motherhood.

Texans have an astounding propensity for voting against our own interests. Maybe we love guns so much that we even relish shooting ourselves in the foot.

“I was having to answer to accusations that were built upon false assumptions, and I was trying so hard to undo the underlying false assumption, finding it impossible to find any headway on that,” Davis said.

She described it as a “can’t win” situation, and Clinton’s in a similar boat. Hell, she’s been sailing that sea of subtext for decades. This year, Davis said, women are listening intently for those dog whistles: “I just love that we’re listening with a more sensitized ear to those things, and we’re calling it out as soon as we hear it in a really powerful way.”

But there’s a catch, and it’s an inescapable one even if women run impeccable campaigns: When women run for executive-level offices, “that’s where we lose some of our moderate women voters.” Davis says she saw this turn up again and again in focus groups her campaign ran with moderate Republican women.

“You wouldn’t believe the percentage of them who said that a woman couldn’t or shouldn’t be governor,” recalled Davis. “Voters will put women into congressional offices and senate offices, but ask them to put them as the commander in chief or the executive office of the gubernatorial mansion, and people will fall back into this gender bias.”

The solution is precluded by the problem. Until we see more women in executive offices, we won’t be comfortable putting them there.

“I think that’s one of the benefits of a Hillary Clinton presidency,” Davis said. “If we can’t see women in those offices, we don’t believe they’re capable of doing a good job in them, and she’ll have an opportunity to help change that dynamic.”

But if the voters aren’t there long-term — all of them, including white folks and white women in particular who are willing to put women in office at the highest level — we’ll continue to see this election, and in turn Clinton’s presidency, as an aberration. Texas Democrats have to capitalize on this 2016 fluke; Davis, for her part, is optimistic.

“You wouldn’t believe the percentage of them who said that a woman couldn’t or shouldn’t be governor.”

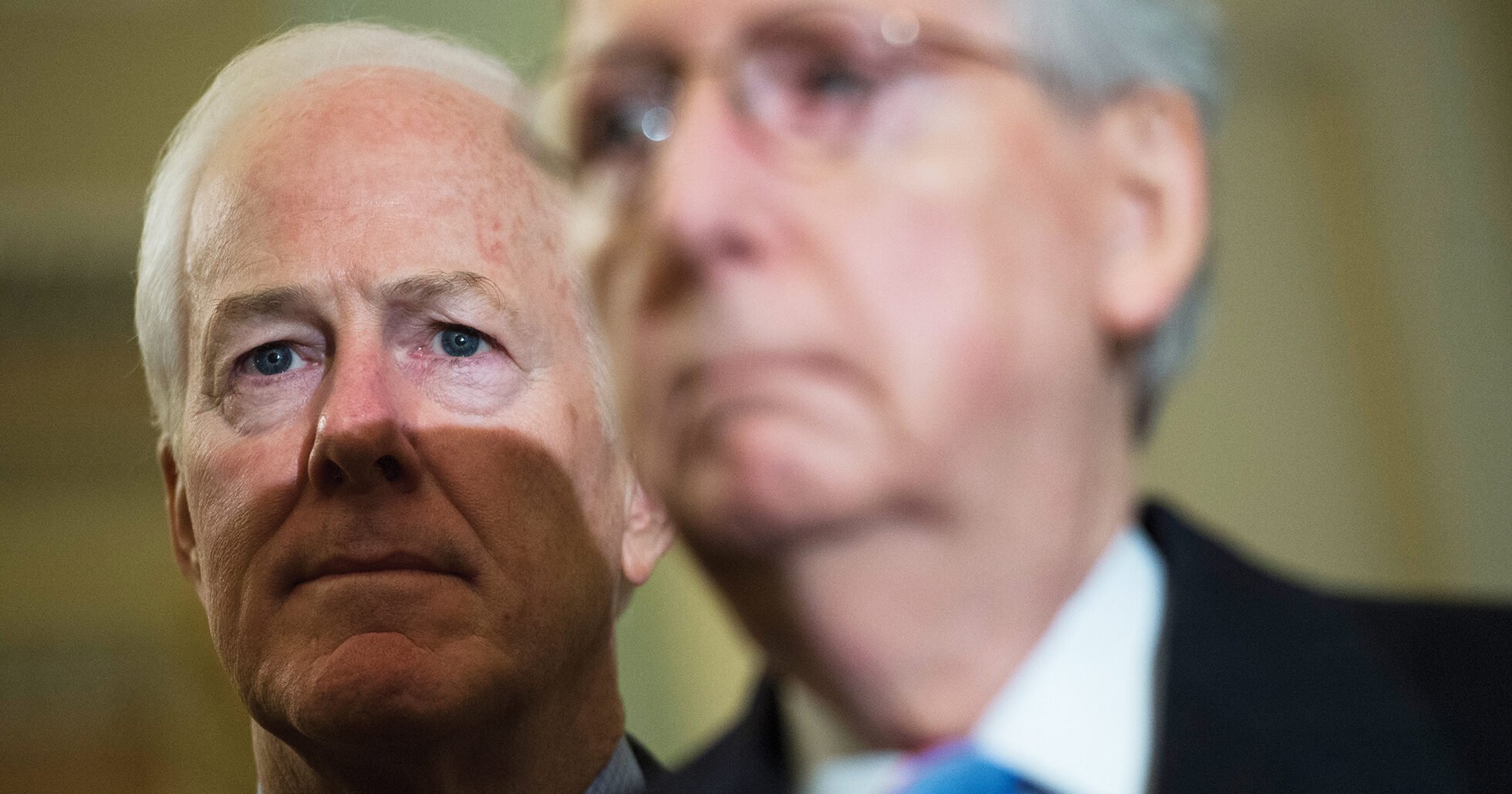

And Republicans have quite a bit of work to do to recover from Trump, particularly as the older white voters — Texas primary voters, who Davis referred to as the “red meat” beast — literally die out.

“They created this dynamic where they’ve got to keep feeding that voter, the voter who wants to hear and see the red meat on abortion, on gays and Muslims,” Davis said.

As millennials and the young voters who are approaching their first elections with more progressive social views become a stronger bloc, Davis wondered: “How do they come back to that voter” after they go extinct? It’ll be tough to walk back decades of anti-woman, anti-gay, anti-immigrant rhetoric, and tough to walk back the fact that the GOP nominated an uber-candidate espousing those beliefs.

In the meantime, until white people scare up a care for Texans of color who are disproportionately harmed by poverty, incarceration, lack of access to health care and the like, and join them in voting for Democrats who might bring a little change to this state, we’ll stay red. I’d likely be beating the same drum if, say, Ted Cruz had secured the GOP nomination. But this election is different. This is, as Erica Grieder at Texas Monthly observed, a “fluky election.”

But Texas is weird, man. Texans have an astounding propensity for voting against our own interests. Maybe we love guns so much that we even relish shooting ourselves in the foot. It’s fine! we shout, hopping around with a holey boot in hand. It’s not so bad, look how free I am!

Maybe, in the end, the Trump backlash and the demographic shift toward a more progressive Texas will end up being one and the same.