Two North Texas Evangelicals Ask: Who Would Jesus Deport?

While white evangelicals remain the main religious supporters of draconian anti-immigrant measures, two prominent North Texas evangelicals are pushing back.

As Texas Republicans and President Donald Trump enact the most sweeping anti-immigrant measures in decades, they’ve been met with fierce criticism from most major religious groups.

Not white evangelicals, though. After playing a key role in Trump’s victory, evangelicals are the only religious group to back the president’s Muslim ban by a large majority. Dallas megachurch pastor Robert Jeffress likely spoke for many when he called for the United States to “say no to immigration and refugees until government starts performing its God-given responsibility of securing the borders.”

Yet some evangelicals in Texas are deeply troubled by the increasing hostility toward immigrants. I spoke with two of them: Darrell Bock, a professor at conservative Dallas Theological Seminary, and Reverend Bob Roberts, a pastor at NorthWood Church in Keller, a solidly Republican Fort Worth suburb.

They’re part of what a recent New Yorker article called a “new moral minority” — a small but growing group of evangelical leaders who, like the Southern Baptist Convention’s Russell Moore, are committed to both biblical orthodoxy and constructive engagement with a changing culture. Roberts and Bock are not liberals, theologically or politically. But they are challenging the nativist, anti-immigrant mindset that pervades the white evangelical community.

Roberts is a prolific tweeter who has a ready smile, especially when he’s talking about his Muslim friends. He was recently mentioned in the Christian Science Monitor as part of a wider movement within evangelical Christianity to build bridges to the Muslim community, fight Islamophobia and become more engaged with global issues such as the refugee crisis. His congregation promotes “open dialogue” with other faith groups. And in 2015, Roberts stood alongside Islamic leaders in Washington, D.C., to denounce anti-Muslim remarks by evangelist Franklin Graham.

Roberts’ outreach efforts seem to be working in Keller: NorthWood Church claims around 3,000 members. He’s also helped to plant around 180 churches across the United States. And he mentors young pastors on building cooperative relationships with people of other faiths and bringing a biblical perspective to issues such as immigration.

Unlike some in the evangelical community, Roberts strongly supports separation of church and state. Nor is he interested in discussing political personalities or parties. “I am not pro-Trump or anti-Trump,” Roberts said. “Trump is my president. Sometimes I agree with him and sometimes I disagree.”

Yet he doesn’t hesitate to challenge, on biblical and theological grounds, the punitive anti-immigration policies coming out of Austin and Washington, D.C.

Earlier this year Roberts joined other national evangelical leaders in publicly opposing Trump’s Muslim ban. Asked his reasons for signing on, he responded with a long list: “The Good Samaritan, the Great Commission, the Golden Rule, the Great Commandment, Matthew 25, the life and model of Jesus, the life and model of the church throughout history — shall we say the Bible!”

If the biblical message is really that clear, why have so many evangelicals turned to suspicion and xenophobia?

Roberts blames what he has called “religious nationalism,” a desire to “take back America” from Muslims and others outside the fold. He believes this movement is rooted firmly in “the fear that the world is changing and we have to keep things as they were in order to survive.” He contends that this fear betrays a lack of confidence in Christianity’s ability to stand toe-to-toe with other religions. “Ultimately,” Roberts said, “people move into the future not by fear but by a new vision of what can be.”

While he says his fellow evangelicals are right to be concerned about security and the rule of law, he challenges them to think beyond those concerns. Christians have prayed for years for the Gospel to reach all ends of the earth, he notes. “It’s hypocritical to pay people to go around the world to tell people about Jesus while stiff-arming those who would come here.”

Dallas Theological Seminary’s Bock challenges his fellow evangelicals to ask themselves a simple question: “Which is better as a symbol for our country, the Statue of Liberty or a border wall?”

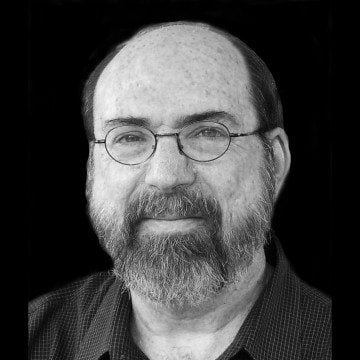

A bearded, soft-spoken man with a slight Texas twang, Bock is a bestselling author, podcaster and frequent contributor to the popular evangelical publication Christianity Today.

Bock argues that the current politics of immigration lacks balance. From a Christian standpoint, he said, it’s a matter of balancing two strands of biblical teaching. On the one hand, he believes Scripture clearly teaches that “a nation has a right to defend her people and be concerned about the direction of her culture.” He has in mind biblical passages that teach respect for the rule of law and are often cited by Christians who favor deporting the undocumented. Yet the Bible also “highlight[s] treating the foreigner with compassion,” he said. Immigration policy must respect that strand of biblical teaching, too.

“ICE crackdowns that lead to fathers or mothers being deported and breaking up families — that’s not a Christian approach,” he said. “Yes, there has been a law violation, but why need it lead to deportation?”

Instead, Bock suggests imposing a fine or putting undocumented immigrants at the back of the queue to gain legal status. In this way, he said, “the law is honored but families are not broken up.” While many progressives will find Bock’s proposal too punitive, it does represent an effort to move past nativist law-and-order thinking.

“Jesus’ call for loving the neighbor applies to all, not some,” Bock said. “So does respect for the integrity of families.”

Bock and Roberts certainly have their work cut out for them. According to one recent study, evangelicals’ views on immigration are shaped more by the media than by the Bible. However, two-thirds of respondents said they would value hearing what Scripture teaches about immigration. If leaders like Bock and Roberts can get their message through to folks in the pews, they have a shot at eroding evangelical support for anti-immigrant policies.

Whether or not that comes to pass, these leaders serve as a reminder that the white evangelical community isn’t as monolithically reactionary as it is sometimes portrayed. They offer an opening for Texas’ emerging but still wobbly progressive movement to do some coalition-building. If progressives can learn to speak authentically about matters of faith and morality while defending church-state separation, we may well find allies — at least on some issues — in unexpected places.