The Great Mellowing

God, Willie Nelson, and the increasingly thinkable pipe dream of marijuana reform.

A version of this story ran in the August 2015 issue.

Willie Nelson is iconic enough as a performer and celebrity, both in Texas and in the broader United States, that casual fans can be forgiven for not remembering that he’s also a writer, and a damned influential one. Sure, as a braided personification of post-hippie spirituality and good times, Willie is a symbol for the history books. As the rare American celebrity who proudly wears his Cherokee heritage as a fashion statement, he’s an emblem of ethnic rapprochement. As a leading activist for farmers and marijuana reform, he’s a political figurehead of sorts. As a troubadour who has come to embody the romance of a professional musician’s life on the road, he’s a vehicle of American wish fulfillment.

Before any of that, however, Willie was a writer, a great American ventriloquist in the Nashville and Tin Pan Alley traditions, writing songs that other people made famous. In the second half of the 20th century, if you heard lyrics that were heartbreaking and true, timeless but as immediate as tomorrow morning’s newspaper, there’s a good chance the words originated with Willie. When Patsy Cline audibly bent heartstrings singing, Crazy, for thinking that my love could hold you, for instance, that was Willie, speaking through her. When Al Green or Elvis Presley greeted audiences with a faux-nonchalant, Well hello there / My, it’s been a long, long time, that was Willie, reminding us of the funny way time slips away.

“I think people need to be educated to the fact that marijuana is not a drug. Marijuana is an herb and a flower. God put it here. If He put it here and He wants it to grow, what gives the government the right to say that God is wrong?”

The list of distinguished (and undistinguished) interpreters of Willie’s words goes on and on, from Roy Orbison and B.B. King to Pet Shop Boys and Donkey from Shrek. The most recent, wittingly or no, is state Rep. David Simpson (R-Longview), who this year adapted a Willie line into an entire legislative bill. The original quote is so ubiquitous on the Internet—including on Willie’s own willienelson.com—that it’s nigh impossible to ascertain where or when Willie first said it: “I think people need to be educated to the fact that marijuana is not a drug. Marijuana is an herb and a flower. God put it here. If He put it here and He wants it to grow, what gives the government the right to say that God is wrong?”

Here’s Simpson’s cover version, from a widely disseminated news release this March announcing a bill that would fully legalize marijuana in Texas: “Current marijuana policies are not based on science or sound evidence, but rather misinformation and fear. All that God created is good, including marijuana. God did not make a mistake when he made marijuana that the government needs to fix.”

Simpson, a tea party Republican who opposes abortion and gun control, may or may not know that he’s covering Willie Nelson here, but let’s analyze the lyrics. Heartbreaking? Check. Nearly 75,000 Texans are arrested every year for marijuana-related offenses, at a taxpayer cost of more than $100 million. True? That depends on your political and religious convictions, but it passes the traditional Nashville songwriter’s test: Listeners buy it. According to a 2014 poll by the University of Texas at Austin and the Texas Tribune, 77 percent of Texans think marijuana laws should be reformed and 49 percent think the drug should be legal for recreational use. Timelessly relevant, but more vital than ever today? Yes and yes, in true Willie style.

Simpson’s bill, which would have set marijuana on the same regulatory footing as “tomatoes, jalapeños, or coffee,” made it out of committee with meaningful Republican backing, an unexpected first for Texas. Though the bill didn’t receive a vote from the House before it expired by procedural deadline, it’s beginning to seem possible that, within a session or two, Texas might actually enact meaningful marijuana reform, and without having to wait for a statewide Democratic resurgence. Funny, indeed—for the architects of the war on drugs at least—how time slips away.

Willie Hugh Nelson was born in Abbott, pop. 356, in 1933 and grew up in a cultural slice of America that has long been hostile to marijuana use. In his new memoir, It’s a Long Story, Willie paints the picture of his childhood in a little house on the Texas prairie, a place defined by religion, family, farming and the fading romance of the Old West. “You might say that I was born in the middle of nowhere, but I feel that I was born in the middle of everywhere,” he writes.

The memoir’s warm affection for traditional small-town culture will be familiar to fans of Willie’s music. For instance, “Family Bible” (1957), the song that first got him noticed as a songwriter:

Now this old world of ours is filled with trouble

This old world would oh so better be

If we found more Bibles on the table

And mothers singing “Rock of ages, cleft for me.”

The cultural shifts of the 1960s—civil rights, the sexual revolution and the growth of a semi-political counterculture centered on marijuana—threatened the traditional values of places like Abbott. Willie’s poker buddy Merle Haggard memorably captured the backlash in his 1969 hit “Okie from Muskogee”:

We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee

We don’t take our trips on LSD

We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street

We like livin’ right, and bein’ free

We don’t make a party out of lovin’

We like holdin’ hands and pitchin’ woo

We don’t let our hair grow long and shaggy

Like the hippies out in San Francisco do.

The traditionalist aversion toward marijuana captured in Haggard’s lyrics soon found a political home in the Republican Party and a policy plank in Nixon’s war on drugs. After a brief armistice during the administration of Jimmy Carter, during which Willie, as he tells it in the memoir, smoked a joint on the White House roof, Ronald Reagan resumed the drug war with gusto, more than doubling the percentage of incarcerated Americans over the course of the 1980s. Democrats eager to appear tough on crime—and to mind their erstwhile Southern populist base—joined forces more or less enthusiastically. For decades, marijuana reform was an untouchable third rail in American politics.

These days, of course, Haggard and Willie are singing a different tune. Their new duet single, released April 20, is called “It’s All Going to Pot.” That title could be taken to refer to an incipient sea change in attitudes about marijuana in places like Abbott and Muskogee—or even Longview, the conservative East Texas city represented by Simpson in the Texas Legislature.

This shift could not be more welcome or necessary. According to a 2013 ACLU report, Texas held a number of unfortunate distinctions in terms of marijuana enforcement in the first decade of this century. We were second in the nation after New York in annual marijuana arrests. We had the greatest increase in pot arrests over the course of the decade (though arrests have more recently declined from a peak in 2009). Black Texans were twice as likely as whites to be arrested for pot; in rural areas of the state, disparities were often much larger. In two rural counties on the far fringes of the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, Van Zandt and Cooke, blacks were more than 20 times more likely than whites to be arrested for pot.

This last detail—the staggering disproportion in drug-law enforcement between whites and blacks—has long been at the core of the left-wing argument for marijuana reform. Willie includes this line of argument by implication in his memoir: “Compared to the injustices suffered by others, I didn’t suffer at all. Ray Charles told me a story about how one of his sidemen was caught with one skinny joint in Houston back in the 50s and, as a result, spent a year in the pen … The thing that gets me is, why? Why waste precious law enforcement resources on this bullshit?”

It’s a good question, succinctly put. A prevalent view on the left, especially after the highly visible recent protests of police abuse and murder of poor black men, would hold that drug laws, unevenly enforced, give cities and towns the leeway to enforce racial and economic barriers (up to and sometimes including white supremacism), to manipulate crime statistics for local political purposes, and to threaten otherwise law-abiding citizens. As journalist and TV creator David Simon (The Wire) put it in an interview that circulated widely after the recent Baltimore riots, “The part that seems systemic and connected is that the drug war … was transforming in terms of police/community relations, in terms of trust, particularly between the black community and the police department. Probable cause was destroyed by the drug war. … It was done almost as a plan by the local government, by police commissioners and mayors, and it not only made everybody in these poor communities vulnerable to the most arbitrary behavior on the part of the police officers, it taught police officers how not to distinguish in ways that they once did.”

Perhaps depending on how much weed you’ve been smoking, what Simon describes is either a case of incompetent policing or a callous strategy to turn a certain class of people into de facto criminals and thereby negate their rights to due process. According to the Mayo Clinic, most Americans (at least 68 percent) take drugs of some kind or another, legal or not. Poorer Americans are less likely to have access to health care, and thus, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, more likely to self-medicate with illegal drugs. Marijuana is by far the most popular, constituting 75 percent of the illegal drug trade in the U.S. Thus, marijuana prohibition gives law enforcement, employers, landlords, etc., an invaluable tool to control and coerce poor and minority populations. Such laws are useful to a plutocracy regardless of whether smoking pot is harmful for anyone involved, much as our current labor market and immigration system deliver the practical benefit of declaring millions of low-income workers in America “illegal” so they can be threatened, harassed or deported without probable cause of any crime other than existing on this side of the border.

That’s the left-wing, equality-oriented argument, at least. Willie never really goes there, at least not in the new memoir. He’s a believer in the power of positive thinking, as he mentions several times in the book, and not one to succumb to paranoia. (The latter has probably been a key to his long, happy relationship with marijuana—“by far the smoothest of all my marriages,” he writes.) He’s also not one to condemn or ridicule the mores of traditionalist America, even when he disagrees with them.

Still, especially looking back at his IRS investigation in the early 1990s, even Willie is inclined to see some funny business afoot among the enforcers of our nation’s laws. He makes the IRS incident the framing story of his memoir, introducing it in the first few pages as the most trying time of his life. “Can’t say for sure, but I have a feeling that in the eighties the federal government was upset by my increasingly public pro-pot stance,” he writes. “The men in charge didn’t like how Farm Aid, the yearly event I’d cofounded, led to discussions about how the government continued to fuck the farmers. By the end of the eighties and the start of the nineties, people were saying that I was a marked man.”

In defense of those who have executed and enforced drug laws, marijuana is not a harmless substance. It’s difficult to research the drug in the United States because of its federal Schedule 1 criminal status, but studies show evidence that smoked marijuana may cause cancer in much the way that smoked tobacco does. A few “pothead” stereotypes are also supported by science: Chronic use can cause problems with learning and memory, processing speed and selective attention. People under the influence of large doses of marijuana are probably too impaired to safely drive or operate other dangerous machinery. Though the “gateway drug” hypothesis has been widely debunked, psychological addiction to marijuana is another serious risk, as with any drug. Finally and most alarmingly, marijuana use has been associated with psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. This last issue seems to affect teenagers genetically predisposed to schizophrenia, who are more likely to develop the condition if they use marijuana, and people already diagnosed with schizophrenia, who are more likely to experience psychotic symptoms when they use marijuana. These risks may not compare to the massive public health problems posed by tobacco and alcohol, but they do merit the attention of a good, liberal government.

Democrats eager to appear tough on crime—and to mind their erstwhile Southern populist base—joined forces more or less enthusiastically. For decades, marijuana reform was an untouchable third rail in American politics.

Willie ought to be as aware as anyone of the hazards of promoting a squeaky-clean image for marijuana just as it’s becoming legally available in several states. “I don’t want to go into a tirade against tobacco,” he writes in the memoir, recounting his father’s death from lung cancer. “This isn’t the time or place to go into the history of an industry that for decades hid the truth about its product’s deadly properties.” Given that the legendary singer is on the cusp of launching his own marijuana brand, Willie’s Reserve, for sale in Colorado and other states that have ended prohibition, one hopes that he will include disclaimers to teens, drivers and heavy smokers about the health risks of his product. Likewise, though liberals should be happy to have libertarians such as Rep. Simpson (who helped organize a fundraiser for Ron Paul in 2008) as bedfellows on this issue, we should also support public health regulation of marijuana that goes far beyond that accorded to tomatoes and jalapeños.

“Pot got me up and took me where I needed to go. Pot chased my blues away. When it came to calming my energy and exciting my imagination, pot did the trick damn near every time I toked.”

On the other hand, marijuana may indeed offer a wide range of health benefits, at least for some users. Our pro-prohibition Republican governor, Greg Abbott, was convinced this year to sign a bill legalizing non-THC cannabidiol oils for narrow use in treating epilepsy. Proponents of medical marijuana use—many of whom, like Willie, have self-medicated with it for years—tend to focus anecdotally on its psychiatric effects (combatting anxiety, depression or PTSD) or its efficacy in relieving pain, spasticity and neuropathy. Willie’s personal relationship with marijuana seems to be half recreational, half medicinal. “Pot got me up and took me where I needed to go,” he writes. “Pot chased my blues away. When it came to calming my energy and exciting my imagination, pot did the trick damn near every time I toked.”

The world Willie Nelson grew up in, as detailed in the memoir, was drenched in alcohol and religion—the wild, disconsolate nightlife and the “straight is the gate” repentance of Sunday morning. What linked the two was music. Young Willie understood this early and moved fluidly between both poles throughout his early development as an artist. He was both a rabble-rouser and a true believer, not to mention an encyclopedia salesman and radio DJ who earned his bread playing the character of a down-home Texan. He had a gift for music and for gab, and looks in pictures and film clips like a goofy, prototypical 1950s young man on the make, sort of a cross between Randy Quaid’s character from The Last Picture Show and a young Richard Nixon.

Willie’s first songs spoke not to the nascent early-’60s counterculture but to what Greil Marcus has called “… Hank Williams’s America, where romance is only a night call.” The small-town Manichean push-pull of liquor and religion, hedonism and matrimony, are evident everywhere in Willie’s early lyrics, from The night life ain’t a good life, but it’s my life to Gotta get drunk, and I sure do dread it / ’Cause I know just what I’m gonna do.

How did Willie make his way from that tortured, alcoholic voice on the AM radio to the laid-back icon of mellowness we all know and love? In his telling, it involved hefty doses of new-age thinkers including Kahlil Gibran, Edgar Cayce and Father A. A. Taliaferro, along with the good old family Bible, where Willie had sought answers since childhood. It also involved a lot of marijuana. Willie kicked whiskey and made pot his full-time steady in 1972. “Liquor agitated me,” he writes. “Weed calmed me. Liquor sped me up. Weed slowed me down. Liquor made me reckless. Weed made me careful. And when it came to two of life’s greatest pleasures—making music and making love—liquor made me sloppy while marijuana made those experiences rapturous. … It pushed me in a positive direction. It kept my head in my music. It kept my head filled with poetry.”

It also helped him, over the course of the 1970s and ’80s, to modernize and renovate the core dichotomy of the country music genre, from hellfire and hell-raising to a wide-ranging spirituality and odes to friendship and hijinks on the road. At the same time, Willie reinvented himself from a fading mid-level star of the Nashville machine to a worldwide celebrity. The romantic ache and wistful nostalgia at the core of so many of his songs remained—apparently, these are byproducts of life on earth, not any specific inebriant—but the rest changed, becoming warmer and more open, growing into what one critic, anonymously quoted in the memoir, would later call “the generosity of spirit that is, in fact, the hallmark of Willie Nelson’s musical aesthetic.”

It’s impossible to empirically determine the influence Willie Nelson has had on the society he came out of and has treated as his core audience for his entire career. Certainly not all of small-town Texas has changed with him, but perhaps enough has. Consider the back-and-forth over Willie’s 2010 arrest in Sierra Blanca, pop. 553, for possession of 7 ounces of marijuana—a felony that should, by law, have meant jail time. First, the county prosecutor offered to cut Willie a deal: Pay a $378 fine and play “Blue Eyes Cryin’ in the Rain” for the courtroom. Then a judge overruled the deal, seeking a harsher penalty. Finally, after reweighing Willie’s stash and finding it inexplicably several ounces lighter than originally recorded, Hudspeth County Sheriff Arvin West altered the charges and sent Willie a $527 ticket for possessing paraphernalia. “The last thing in this world I want to be is a pothead hero,” West told Texas Monthly. “But the laws we’ve got now don’t work. Something’s gotta change.”

The prospect of a right-left coalition on marijuana reform could be, as Willie suggested to Rolling Stone last year, just a side effect of the fact that “a bunch of old, ignorant white people … are dying off.” Or it could be that Willie himself has changed enough minds that his more conservative fans can finally brook the idea of supporting the anti-prohibition agenda of a figure such as Rep. Simpson. And if so, who knows what other culture war issues may someday follow, as the shift that captured Willie’s imagination in the early 1970s finally catches up with traditionalist Texas.

“I’m writing my long story at a time when the tide has finally turned,” Willie writes toward the end of his memoir. “The idea of legalizing marijuana, whether for medical or recreation reasons, is more popular than ever. The majority of rational people have concluded that the plant is not a menace to society but can actually do good. This has been my argument for a good half century.”

It’s an argument that Willie has lived by example and shared with fans through his music. Now he’s beginning to hear it echoed back to him from the halls of power. Classify these as good times.

Still, the fight in Texas is by no means won. It’s no exaggeration to say that marijuana prohibition still ruins thousands of lives in Texas every year. Meaningful reform will require the support of many more Republican legislators, as well as party leadership and the governor. Here’s to hoping that Simpson’s rendition of Willie’s old line about legalization is not the last cover version we hear, that it catches on and becomes a more and more familiar refrain—and perhaps, sooner than we would have expected, an American standard.

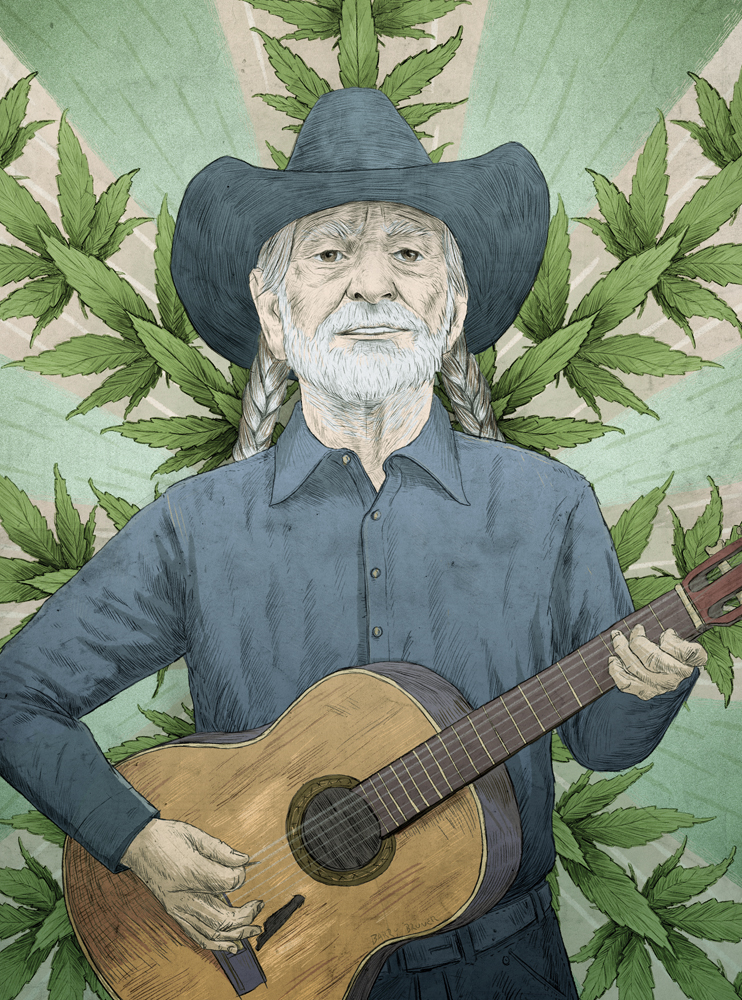

Header photo by Drew Mackie/Flickr.