With Sprawl and Serial Killers, Houston Noir Packs a Mean Punch

As characters flit from one unzoned neighborhood to another, this new short story collection explores the city’s identity through crime.

Houston has long been in search of an identity, as opposed to a nickname (Space/Bayou/Magnolia City). The separate elements of the South, the West, the oil industry, the port and NASA don’t come together easily.

That’s probably why some residents embraced Hunter S. Thompson’s 2004 description of Houston as a “shabby, sprawling metropolis ruled by brazen women, crooked cops, and super-rich pansexual cowboys who live by the code of the west.” One fan proudly displayed this fanciful description on a giant banner at the 2016 NCAA Final Four.

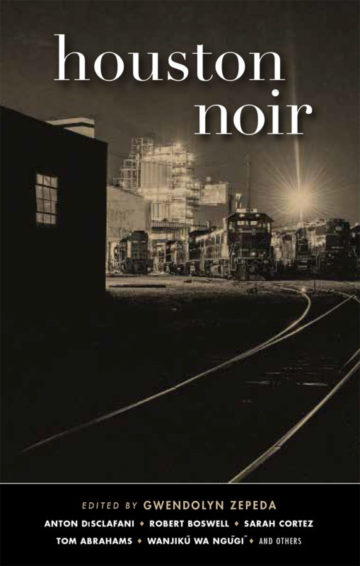

Edited by Gwendolyn Zepeda

Akashic Books

$15.95; 256 pages

In the last decade or so, Houston has developed another, more palatable identity — that of being the country’s most diverse city. A new short story collection, Houston Noir, seeks to combine those two identities in one multicultural and appealingly dark mix, and mostly succeeds in doing so.

Houston comes late to Brooklyn-based Akashic Books’ Noir series, which asks local writers to set crime stories in specific neighborhoods in order to create a portrait of the city at large. Crime reveals character, apparently.

This is the second story collection in recent months to include a Houston road map. Like Bryan Washington’s celebrated Lot, Houston Noir includes site-specific stories with a general focus on grit rather than glamour.

So what is the portrait of Houston that emerges from these stories, assembled by editor Gwendolyn Zepeda, a novelist and the city’s first poet laureate? The city sprawls massively, for sure. Spring and Clear Lake are 45 miles apart. And it’s a drivers’ city. The characters in many of the stories flit from one neighborhood to another. But that boundaries are fluid in our unzoned city is a key strand in our collective DNA.

Speaking of fluid, since the floods of recent years, culminating in Harvey’s 50-plus inches of rain, we’ve also got dirty water on the brain, as reflected in Tom Abraham’s oozy “Tolerance,” which follows a swamp-thing of a cop as he investigates a series of murders of sex workers.

Again, driving and traffic make life both possible and problematic. In “The Falls of Westpark,” the enigmatically pen-named Pia Pico makes the reader feel how traffic, and strategizing about traffic, wears on us and maybe even makes us more susceptible to mayhem.

This version of Houston is infested with serial killers. Too many, really. The second half of the collection is mostly taken up with these scenarios. Some are better than others — Abraham’s story is the most chilling — and the dangers immigrant women of color face on our streets is an important Houston story. But the strongest story about human trafficking, Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton’s “Where the Ends Meet,” breaks from the mold to deal directly and sympathetically with a morally conflicted trafficker.

Hunter S. Thompson would’ve read Robert Boswell’s “The Use of Landscape” with glee. In the book’s River Oaks entry, Boswell hilariously and gleefully burns the world of the “super-rich pansexual cowboy” to the ground. Boswell, of the University of Houston creative writing faculty, appears to have the most fun with his assignment: “The party moved to River Oaks. Madelyn’s house was not big by neighborhood standards — barely the size of an ocean liner.”

The collection could do more to capture the city’s diversity. Since Houston is home to Halliburton and Enron, not the mention most of the state’s oil and petrochemical industries, the collection could use more white-collar and industrial crime. Of course, it’s easier to ask for these stories than to actually produce them. In other words, the collection is strong enough that I wish it were longer.

One piece with a memorable storyline is Adrienne Perry’s “One in the Family,” about a homeless vengeance-taker’s making her way through the city’s cultural landmarks as she gears up for a chilling payback.

The most singular story might be Reyes Ramirez’ “Xitlali Zaragosa, Curandera,” which tells of a woman who practices old Mexican traditions to banish bad spirits, even if it means alienating her Americanized daughter. There’s sadness here, but no crime as such. I’d be happy to read more of the curandera’s melancholy adventures.

Is all crime fiction “noir?” Maybe, but some writing is certainly more “noir” than others. That is, it features snappy lines spoken or thought by characters caught up in their fates. Abraham’s description, “She was clothed in a torn pink dress that clung to her body in a way that would’ve been unflattering on a breathing woman,” fits the bill. From “Happy Hunting,” Icess Fernandez Rojas’ line, “That was the East Side: more connected than a politician and only half as shady,” may come closest to the “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown,” beau ideal. The book closes with Stephanie Jaye Evans’ icepick of a farewell, from “Jamie’s Mother”: “Thank you, she thought. Probably to God.”

Since these are the last thoughts of a woman whose mission of revenge has taken a fatal twist, the line packs a mean noir punch. Houston Noir is a welcome addition to the city’s slowly filling bookcase.