Report: Mexico’s Border Crackdown Sends Migrants into Dangerous Territory

In July 2014, Mexico announced its Southern Border Plan — with backing from the United States — which Mexican officials claimed would bring order to Mexico’s influx of Central Americans while protecting their human rights.

Two months later, President Obama would praise Mexico’s new border strategy, crediting it with reducing migration at the U.S.-Mexico border. The number of unaccompanied minors apprehended by U.S. Border Patrol had been reduced by more than half.

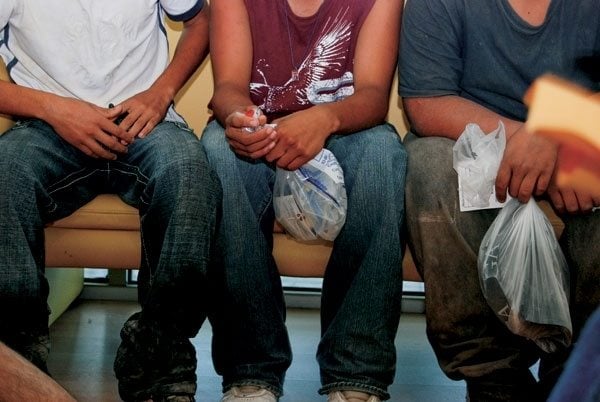

But according to a new report, Mexico has provided few protections for refugees fleeing violence in the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. Instead, Mexico has set up a massive deportation system that rarely offers political asylum. The border crackdown has also forced more migrants into rugged and remote areas in Mexico, where many are robbed or exploited by criminal groups.

The report, produced by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) in collaboration with two Mexican nonprofits, found that deportations along Mexico’s southern border more than doubled between 2013 and 2015, up from 86,298 to 198,141 in 2015. And very few migrants are filing for political asylum, despite being victims of violence and persecution in their home countries.

“Mexico should be granting more asylum requests, but it’s not,” said Maureen Meyer, senior associate for Mexico and Migrant Rights at WOLA. “Migrants aren’t aware they’re able to ask for asylum, or they are persuaded not to try. And if they request asylum, they are held in detention. This prevents a lot of people from applying.”

Of the nearly 100,000 people who have been apprehended on Mexico’s southern border this year, fewer than 3,500 have applied for political asylum. Very few will be accepted, said Meyer. Of the 420,000 migrants detained between 2014 and July 2016, Mexico granted only 2,800 asylum claims.

Along with the report, WOLA has released a series of videos highlighting Central American migrants who had credible asylum claims in Mexico, but who were deported to their home countries, putting their lives in jeopardy.

Meyer said one of the biggest challenges is convincing officials in the U.S. and Mexico to view the Central American migrants as refugees, which would make them eligible for protection under international treaties. “The refugee crisis in the Northern Triangle doesn’t fit the traditional pattern: that they are fleeing because of war. There isn’t a war. But they are experiencing the same level of violence and trauma.”