Woody Lived Here Too

A version of this story ran in the October 2013 issue.

Those who enter Woodyland always come out changed, or at least that’s what Johnny Depp and Douglas Brinkley claim in their introduction to Woody Guthrie’s previously lost novel, House of Earth. They were surely referring to “Woodyland” more as concept than geographic location, but after the book was released in March, my father, a music historian and retired Abilene librarian, suggested we make a pilgrimage to Pampa, the Panhandle city where the novel is set, and where Guthrie lived from age 17 to 25.

by Woody Guthrie

Harper

288 pages

$25.99 Harper

As we drove through a string of small prairie towns, my father played his favorite Woody Guthrie compilation on repeat. Dad, like much of the boomer generation, had been introduced to Guthrie’s music via Bob Dylan (which my father and his friends, growing up in Denton, naively pronounced “Die-lan”). Listening to Woody sing about how “some will rob you with a six-gun / some with a fountain pen,” one could be forgiven for thinking that Guthrie’s vocal stylings, his nasal way of talking through a song, had been unabashedly ripped off by Mr. Die-lan.

In Spur we ate at a Dairy Queen, the interior of which was covered in wood paneling and black-and-white photographs of Quanah Parker. We passed through Turkey, the home of Bob Wills. The sunburned dirt became redder and angrier the farther north we drove, cottonwoods lining dry creek beds, fields of budding wheat, hay and Johnson grass stretching into the horizon. The deserted highway began to slice through sharp, rust-colored canyons, here called “the breaks” of the Caprock, some of which are bottomed with salt flats. And then we were atop the escarpment: Woodyland.

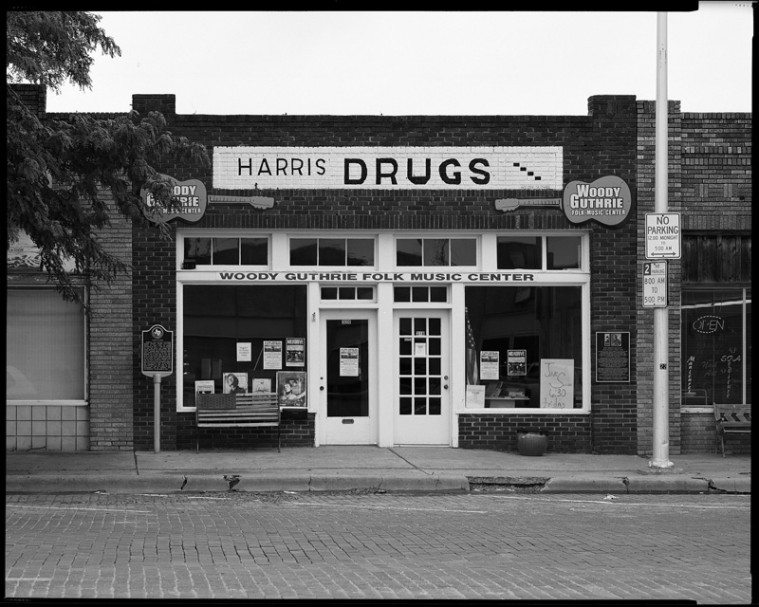

Not many people associate Guthrie with the state of Texas—after all, he was born in Oklahoma, became famous singing in California and New York, and his best-known song, “This Land Is Your Land,” never mentions the Lone Star State. But it was here in Pampa (current pop. 18,000) that a teenage Woody learned to play the guitar he found in a back room at Harris Drugs, where he had a job pulling soda in the small redbrick building that still stands at the edge of the historic downtown, and is now home to the Woody Guthrie Folk Music Center.

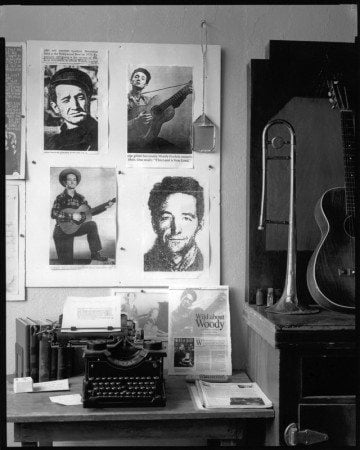

The building contains one long, thin room and a stage in the back with amplifiers and music stands to accommodate the jam sessions that occur here weekly. The walls are covered in handmade posters detailing all things Woody: newspaper clippings, maps of Pampa highlighting Woody-era landmarks, music festival posters, photographs of Guthrie relatives who’ve visited (including Arlo with his crazy hair) and even a cardboard silhouette of Guthrie’s guitar, with its famous motto—“This Machine Kills Fascists”—written across the soundboard.

There’s a section of wall dedicated to the 1935 Palm Sunday dust storm, including photographs of a cloud approaching the little oil boomtown so big and black that I could see why folks thought the end times had arrived. Guthrie was in Pampa for that storm, holding a wet rag over his mouth as all around him houses filled with dust and car engines and cattle choked to death. It inspired several of his more popular songs, including “So Long, It’s Been Good To Know You,” as well as House of Earth, though the novel wasn’t written until a decade later.

home to the Woody Guthrie Folk Music Center, where open jams begin each Friday at 6:30 p.m. Charles Henry

The Woody Guthrie Folk Music Center’s board members all showed up to meet my father and me. Founder Thelma Bray, almost 90 years old, wore a blue ribbon tied in a bow around her neck, silver heart earrings and perfectly coiffed white hair. She showed us a lace curtain from the historic Schneider Hotel, still grubby brown from the 1935 storm’s dust.

I pointed to the beautiful wooden bar that stood along one wall. “Where did he keep the Jamaican Jake?” I asked, referring to the bootleg liquor that Woody sold alongside the soda, at least according to his colorful autobiography Bound for Glory. Thelma frowned. (Later, we were passed a folded note letting us know that she didn’t like to talk about Woody’s “darker” side.) “That’s not the original bar,” she said. Even the hand-painted “Harris Drugs” sign out front was new—the one painted and signed by Woody had been sandblasted in the 1970s.

I expressed surprise. By the 1970s Woody Guthrie was a household name.

The board members sighed, explaining that even today, “official Pampa” has not fully embraced the Guthrie legacy. Last year, to mark the 100th anniversary of Woody’s birth, they requested city approval to rename a two-block stretch of Russell Street, where Guthrie had lived with his first wife. The request was denied, and only later was the board allowed to put up a memorial sign, as long as board members “didn’t make a big deal out of it.”

The reluctance to claim Woody Guthrie as a son of Pampa turns out to have roots that stretch back decades.Woody left Okemah, Oklahoma, in 1929, after his mother, suffering from the Huntington’s disease that would later kill him, too, was institutionalized. He followed his wayward father to Pampa, where the elder Guthrie was running a seedy flophouse. “Pampa was a Texas oil boom town and wilder than a woodchuck,” Guthrie wrote in his autobiography, and though he lived there for just eight years, the town’s influence on him and his music was undeniable. He became friends with the local librarian, spending whole days reading biographies of Abraham Lincoln and the poetry of Khalil Gibran. He learned to make art in Pampa, and eventually acquired the requisite guitar chops to perform at area dance halls with his first band, the Corn Cob Trio.

When Guthrie was 21 he married a local girl named Mary Jennings. The couple had three children and lived, not particularly happily, in a tiny shotgun shack near downtown Pampa. Joe Klein, in his excellent Woody Guthrie: A Life, writes about how, years later, after he and Mary were separated, Woody brought a young Pete Seeger through town, and “[t]hough Pete was prepared for something less than a mansion in Pampa, he was surprised by the dumpy little shack that Mary and the kids were living in.”

The Great Depression, meanwhile, was washing over the Texas Panhandle, and Woody became restless. In 1937 he began taking off regularly, hitchhiking and jumping trains to California and back, staying in migrant camps, where he became politicized. He eventually came to rest in California and began making a name for himself on the radio. But though he never returned to live permanently in the Panhandle, the Dust Bowl conditions of North Texas and the red canyon landscape of the Caprock stayed with him, not only in the lyrics to dozens of songs, but eventually in the only novel he was ever able to finish.

We know that Guthrie worked on and abandoned several books after the successful publication of Bound for Glory, and for decades his rumored “adobe novel” was categorized as one of these unfinished works. Then, a few years ago, while researching Bob Dylan for a Rolling Stone article, Rice University history professor Douglas Brinkley stumbled upon the complete manuscript among the papers of filmmaker Irving Lerner, to whom Guthrie apparently sent it in hopes it would be made into a film.

House of Earth tells the story of Tike and Ella May Hamlin, who barely subsist on their small Panhandle farm, first as renters, then—and worse—as sharecroppers. No matter how hard they work, the system is stacked against them, or as Tike says, “Why has there got to be always something to knock you down?” The entire novel takes place within a small radius of the shack where they live. From the beginning, when they are told by an older relative to “Get a hold of a piece of earth for yerself … Wood rots,” their thin, termite-ridden, freezing-cold-burning-hot shack comes to represent all that is wrong with a world in which bankers and landowners hold all the power. Tike sends away for a government pamphlet detailing how to build an adobe house—lasting, insulated, made of dirt readily available to anyone—and this becomes the dream house of the title, a house to free working people from bondage.

Though Joe Klein didn’t know about the House of Earth manuscript, his biography of Guthrie does mention Woody’s obsessive interest in adobe home construction as a tool for political revolution. In 1936 Guthrie gave his friend and former Corn Cob Trio bandmate Cluster Baker a painting of an adobe house, and on the back he’d written, “This is adobe, a painted clay, open air and sky. I was painting in front of the Santa Fe art museum when an old lady told me, ‘The world is made of adobe,’ and I said, ‘So is man.’”

In their introduction, a beautifully written panegyric to both Guthrie and his novel, Brinkley and Depp argue that while Guthrie “knew more about the Caprock country than perhaps any other creative artist who ever lived” (I’m not sure Butch Hancock, Andy Wilkinson or Dan Flores would agree), the novel “could just as easily have been set in a Haitian shanty-town or a Sudanese refugee camp as in Texas.”

While it’s certainly true that Guthrie’s political message has universal implications, it’s also the weakest part of the novel. Aside from its repetition, it’s hard to believe that Tike and Ella May just wake up one morning, suddenly a labor union of two, caricatures who spout entire pages about how the banking and agriculture industries are keeping them down.

The parts of the novel I love most are the moments when the universal is submerged in the particular, the parts that couldn’t be set anywhere but the Depression-era Texas Panhandle. Guthrie’s descriptions of the Caprock country reveal it as a land of extremes: “A world close to the sun, closer to the wind, the cloudbursts, floods, gumbo muds, the dry and dusty things that lose their footing in this world, and blow, and roll, jump wire fences, like the tumbleweed, and take their last earthly leap in the north wind…”

Later in life, living in New York, Guthrie would chide younger songwriters with the fiction writer’s dictum of “show, don’t tell,” and the best parts of House of Earth unfold when he takes his own advice, allowing Tike and Ella May to emerge as real people in the domestic sphere: “Spill it,” he says when she’s being too quiet. “Don’t try to set on it like an egg an’ hatch it. Spill it.”

Even more pleasantly surprising is the progressive shade of Tike and Ella May’s relationship, possibly based on Guthrie’s passionate and complex second marriage to New York City dancer Marjorie Mazia. There’s a near-equality in the way Tike and Ella May work side by side, in how she helps in the barn as he helps her paper the walls for winter. There’s even a generous give and take in their adventurous and explicit sex scenes (very racy for their time, and possibly one reason the novel wasn’t published in Guthrie’s lifetime) and a warmth in their frequent teasing. “I got a hell of a lot pertier gal than you that I meet ever’ day right there in that cowshed,” Tike says, and then “wiggled his hips, his rump … his elbows up and down in the shadows that flickered from the cookstove where she laughed.”

Guthrie’s affection for the Depression-era Panhandle and its inhabitants, however, was not returned, especially after Guthrie made it big. Whenever he traveled back through Pampa, according to Klein, the singer-songwriter was treated like an outcast, rumors swirling that he was handing out Communist pamphlets and “talking against God.”

It’s not unusual for an artist’s hometown to lag behind the appreciation gravy train—just look at Lubbock and Buddy or Port Arthur and Janis. Still, such towns usually come around, at least to the idea of tourist dollars. But even in 1992, when Thelma Bray suggested that Pampa acknowledge and take advantage of its connection to Woody Guthrie, not one person at the Chamber of Commerce meeting volunteered to help. Someone even stood up and protested, hissing, “Woody Guthrie was an atheist and a communist.”

Though it was true that Woody played for a number of “red” rallies over the years, the Guthrie supporters at the Center didn’t put much stock in this kind of thinking. Woody wasn’t a communist, they say, so much as an activist for the working class, an artist willing to tell the stories of the down and out. The Guthrie Center’s board members like to quote his famous saying, “Left wing, chicken wing, it’s all the same to me.”

When I asked if they see Pampa becoming more accepting of Woody’s legacy, Sherry Wallace, quiet and thoughtful in her blue jeans and work shirt, said, “Maybe 50 years from now.”

Joe Weaver, vice president of the board, shaking his head, told me, “They teach the kids [in school here] all kinds of patriotic songs, but not ‘This Land.’”

“That’s why it’s important we’re here,” said Mike Sinks, a retired union man and musician wearing khakis and sporting a goatee. Mike became involved one day when he was down the street getting his hair cut, and the barber encouraged him to go next door for a jam session that was in progress. Afterwards, a woman came up to Mike and said, “We need your help!” He thought she wanted something heavy lifted, but she meant much more. Now he is the board’s president.

Despite local opposition to each move the board has made to memorialize Guthrie, this small group’s passion has already gone a long way toward spotlighting Woody’s connection to the Panhandle. Besides restoring Harris Drugs and hosting memorial music festivals, they’ve commissioned a park sculpture honoring “This Land Is Your Land” and had part of U.S. Highway 60 named after him.

How does the sudden emergence of House of Earth, this lost Pampa novel, change our understanding of Woody and Texas? Or does it? Was he truly a “Shakespeare in overalls,” as Alan Lomax once claimed?

While the reviews of House of Earth have been mixed (Larry McMurtry didn’t think much of it), Brinkley and Depp argue that the novel “has a literary staying power that makes it more than just a curiosity: homespun authenticity, deep-seated purpose, and folk traditions are all apparent in these pages.” Which is exactly what fans have said about Guthrie’s music since his first radio appearance.

We can’t know what might have happened if House of Earth had been published 70 years ago, whether it would have been placed alongside Steinbeck’s classics or ended up obscure and out of print. And while some people still listen to and sing Guthrie’s songbook, I would argue that his real importance to American history is not so much his output as his influence. As Klein writes, Woody Guthrie “wandered onto the stage of Forrest Theater and breathed some life into a dying tradition.” Without Woody Guthrie, would there have been a Sixties folk music revival? Would there have been a Seeger or a Dylan or a Baez? Maybe, but certainly not in the form they ended up taking. Woody is a hero to folk music, and all that it became, in a way that he’ll never be to American literature.

Woody Guthrie wrote some powerful and important songs—he was a wordsmith and, in many ways, a genius. But his best work comes out of an oral tradition, written for the ear more than the eye. Even he seems to understand this when, in Bound for Glory, he explains, “… with a song, you sing it out, and it soaks in people’s ears and they all jump up and down and sing it with you, and then when you quit singing it, it’s gone, and you get a job singing it again.” House of Earth, while intriguing and entertaining in many ways, will never have the same effect.

In Pampa, as the board members of the Woody Guthrie Folk Music Center asked me to sign a boxcar mural memorializing Woody’s train-hopping days and sized me up for a “Woody Guthrie Lived Here Too” T-shirt, I began to wonder if the novel isn’t more important to us as Texans than it is to Guthrie’s legacy as an artist.

House of Earth reminds us of the hardships people endured to make this state what it is, and of the populist roots that run through our past, whether chambers of commerce deign to recognize them or not. The novel affirms that Texas is not a monolith, not just a mass of political red, but rather something more complex. Even today, Texans are still a people looking for a house of earth among what the book calls this “vast and undying beauty, the dynamic and eternal attraction, the lure, the bait, the magnetic pull that, in addition to their blood kin and salty love for the wide open spaces and their lifetime bond to and worship of the land, caused not only Ella May and Tike Hamlin but hundreds of thousands and millions and millions of other folks just like them to scatter their seeds, their words, and their loves so freely here.”

Mary Helen Specht’s fiction and nonfiction have appeared in numerous publications, including The New York Times. A former Fulbright Scholar to Nigeria and Dobie-Paisano Writing Fellow, she currently teaches creative writing at St. Edward’s University in Austin.