WTF Sine Die: #TxLege History Edition

The Texas Legislature bids us goodbye today: For the next 19 months—barring a special session on school finance—the state’s residents are more or less safe, as long as you avoid Kory Watkins and Borris Miles. It’s a session that has seen its fair share of comic interludes, and Texas has once again kept secure its nationally renowned status as a nutty state for politics.

But in many ways, the Texas Legislature is probably calmer and more professional than it has ever been. For much of the state’s history, the session was a time where men from far-flung reaches of the state came to a relatively large city to booze and whore for five-month interludes before returning to the Gulf coast or the Panhandle or Highland Park. That held true for longer than you might expect. Billy Lee Brammer wrote in Texas Monthly in 1973 that “the Capitol itself, along with all House and Senate office buildings, is honeycombed with secret lovenests.” The past is filled with many fine statesmen, of course; one shouldn’t generalize.

To be sure, there’s still boozing and whoring, though probably less, and definitely done more discreetly. But in other areas, things are, in many ways, better. Until relatively recently, many legislators had no office at the Capitol and no staff to speak of. With less public scrutiny, they were even easier pickings for the lobby, which operated with zero transparency. Austin’s brothels, no great secret, did a healthy trade. And legislators faced a generally more forgiving attitude from the press corps.

There are still ignorant and corrupt legislators. The lobby still watches each incoming freshman class like vultures. But on the whole, the dysfunction of the recent past can’t hold a candle to its historical counterpart.

Here’s a very short list of some highlights. If you have a favorite story—one that ought to be here—email it to me at [email protected] and we’ll add the best ones.

Masonic cabals!

The Legislature can, at the best of times, sort of run the state, so imagine the sheer drama of watching its predecessor, the Congress of the Republic of Texas, run a nation. It was filled with rough men, and they often had a rough go of things.

On April 14, 1838, President Sam Houston gave an address to a joint session of Congress. Just after, Thomas William “Peg Leg” Ward, a fearsome Irish-born Texas pol, hit Francis R. Lubbock, then the Republic’s comptroller, with a stick. (History does not specify that the stick was, in fact, Peg Leg’s leg, though it is fun to think so.) Lubbock pulled a derringer and fired, with only the “timely intervention of a bystander” preventing Lubbock’s aim from being true.

The two were arrested and brought before the Senate, but, as is recorded in The Texas Senate: Volume I, Lubbock was “honorably discharged” from his arrest by Sen. Jonathan Russell. Both were brothers in the Holland Lodge, a Masonic organization that met in the Senate chamber and was instrumental in setting Republic policy. The group counted eight of the upper chamber’s 17 senators as members. Poor Peg Leg, the guy who was the one actually shot at, was officially reprimanded.

Volume I goes on to note, cautiously: “It is interesting to note that Lubbock earlier had sold his warehouse to be converted into an official residence for President Houston, also a Mason.”

Shady real estate deals involving Texas’ chief executive? Things really have changed.

Coups!

We had some tense committee meetings this session, and some tense floor debates. None match the furor caused in 1870, when a bill authorizing the governor to declare martial law and deploy the state militia hit the Senate floor.

When 13 senators opposed to the bill left the chamber to deny the Senate a quorum, and bolted the door of their conference room behind them, the radical Republicans who ran the Senate sent the long arm of the law after them. Windows of the room were smashed, and the senators were arrested. The Republicans voted for the militia bill without them. They released four—just enough to maintain a quorum—and kept the others under arrest for some three weeks while they passed bills.

When one senator involved in the walk-out, E.L. Alford, was stripped of his seat and a special election selected his replacement, Alford came to work anyway. His elected replacement had to sit in the wings.

Next session: Bob Hall passes his EMP bill—by any means necessary.

Heroes!

A frequent complaint among tea partiers is that no one in Austin reads the bills they pass. But even here, things are better than they used to be, in part because of the addition of legislative staff.

In 1969, state Rep. Tom Moore introduced and passed a resolution through the House, honoring a man he said had done important work in the field of “population control.”

This compassionate gentleman’s dedication and devotion to his work has enabled the weak and the lonely throughout the nation to achieve and maintain a new degree of concern for their future. He has been officially recognized by the state of Massachusetts for his noted activities and unconventional techniques involving population control and applied psychology.

The resolution honored Albert DeSalvo, otherwise known as the Boston Strangler.

Shootouts!

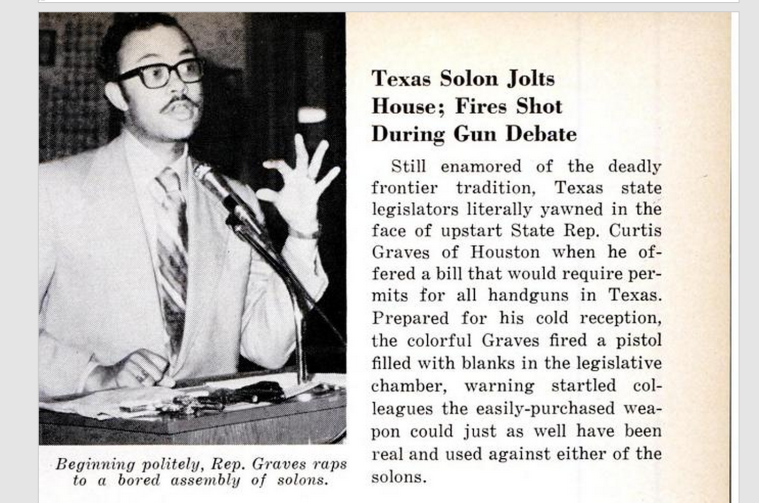

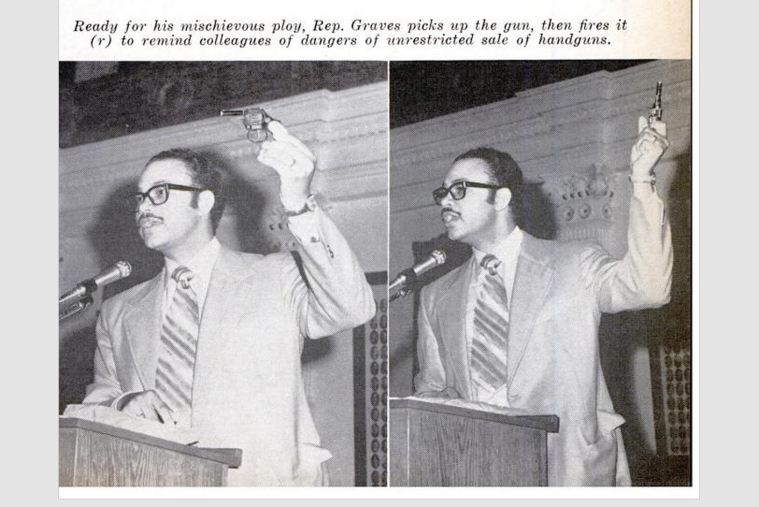

State Rep. Curtis Graves, a liberal African-American legislator from Houston elected in 1966, had to improvise in order to be heard. Once, he railed against a tax bill by standing and yelling on the House press table. In 1971, concerned about measures that made it easier to purchase handguns—thankfully, an issue we no longer face—he took the back mic in the House, pulled a revolver out of his pocket, and fired twice at the House ceiling.

Please, nobody tell Stickland (R-Highlander).

Ballads!

Writeth Paul Burka, in 1976, of one of the greatest Sine Die nights ever:

The scene on the floor of the House was bedlam: representatives clustered around the Speaker’s desk whispering advice; others gathered at the back microphone bellowing for recognition; and smaller groups huddled at scattered spots across the giant chamber where members passed rumors or strained to hear them. It was the closing hour of the 1971 regular session of the Texas Legislature, and the legislative process had broken down under the weight of the Sharpstown Scandal.

The heavy-handed tactics of Speaker Gus Mutscher, under attack for shepherding two suspicious-looking banking bills through a previous special session for discredited Houston promoter Frank Sharp, had divided the House into three groups: blind loyalists, troubled conservatives, and a coalition of liberals and Republicans known as the Dirty Thirty. A huge backlog of legislation was hopelessly stalled, and time was running out. Would Mutscher ask the governor to call a special session? Or would he order the hands of the clock turned back at midnight, extending the session while he tried to arm-twist members into passing a few of the more important bills? Or perhaps he would make a dramatic appeal to the House, asking members to put aside animosities and try to pass something in the little time remaining.

“May I have your attention, members?” Mutscher for once had no trouble with this request; all eyes were on him. “The Chair recognizes Mr. Nelms.”

The legislators were stunned. Why Nelms, everyone was thinking. Johnny Nelms of Pasadena was only a freshman, and a mediocre one at that. What could he do? The silence was broken by the sound of a guitar. Johnny Nelms could sing, that’s what he could do. And as the clock at the back of the chamber ticked away the final minutes of Gus Mutscher’s hegemony over the House, Johnny Nelms serenaded his colleagues with a song the Speaker particularly liked. It was called “Everything I Touch Turns to Dirt.”

Shortly after, Mutscher was indicted.

Anuses!

Earlier this session, Rep. Harold Dutton quizzed Rep. Stuart Spitzer about his sexual history, in what some felt was a session low point for the gentlemanly decorum the Texas House has become world-renowned for.

That’s nothing.

In 1993, state Rep. Warren Chisum, terrified that the state’s ban on sodomy would someday be overturned, offered an amendment that was very nondiscriminatory—it would have banned everyone from having anal sex. Chisum read his amendment, though he said it was “quite offensive to me to have to read it in public.” The amendment would make it a Class C misdemeanor for the “sexual organs” of one person to touch the “anus of another.” The following debate ensued:

State Rep. Debra Danburg: You’re trying to criminalize behavior between the opposite sex, is that right?

Chisum: That’s right.

Danburg: Even if they’re married.

Chisum: More especially if they’re married. Can’t believe anyone would do that if they were married.

Danburg: Even if it’s consensual.

Chisum: Under any circumstances.

Danburg: Even if they slip. Is that right, Mr. Chisum?

[laughter]

Chisum: A violation of the law is a violation of the law.

Danburg: OK, Warren. […] Say my husband and I were having intercourse, and it slipped. And it touched my anus. Do I need to go turn myself in to some health official?

Chisum: I would suggest you see a doctor about his aim.

~ Bonus Whitmire! ~

This session, a couple senators—though especially poor state Sen. Don Huffines—got the full-on Boogie treatment from state Sen. John Whitmire, who from time to time feels his ire rise on the Senate floor and verbally, brutally bludgeons his opponents like a partially-reformed loan shark collecting gambling debts.

This doesn’t really belong on the list, but at the end of this session in particular it needs to be seen. Here’s Whitmire giving the full dressing-down to then freshman state Sen. Dan Patrick in 2007:

They’re debating the budget. Patrick has suggested that there are $3 billion in cuts to be made, and Whitmire smells bullshit. He starts pacing and throwing fingers around.

“Give me the method of financing that you would use to make those cuts. It’s your time to show this body that you know what you’re talking about. Give us the $3 billion in cuts,” he half shouts. “And take your time.”

“I will take my time, senator,” Patrick says, “and I do know what I’m talking about. And I don’t have to stand here and be lectured by you.” To which Whitmire shouts: “Let’s GO!”

Patrick: “I don’t have to be lectured to by you.” Whitmire shouts back: “You can dish it out but you can’t take it, huh?

It goes on for a while. The whole thing is worth watching, with headphones, if the Legislature entertains you. Eight years later, Whitmire is still a shouty, fierce maniac who terrifies freshmen. And Patrick still wants to cut government, but doesn’t seem to know now. The more things change …