ZACH Theatre’s ‘The Great Society’ Lectures More Than it Entertains

By sticking too close to history, Robert Schenkkan gives LBJ a pass.

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Robert Schenkkan’s The Great Society opens as his previous play All the Way ended: Lyndon Baines Johnson has just won the 1964 presidential election in a landslide. Flush with his victory and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, LBJ wisely uses this mandate to pass the historic Great Society legislation — from the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to Head Start, Medicare and public broadcasting — that today, a half-century later, is under fire again.

While All the Way covered the tumultuous events of one year, The Great Society — now at Austin’s ZACH Theatre — attempts to encompass LBJ’s first full term as president in three acts, three hours and two intermissions. That’s a mighty tall order, and one the play fails to deliver.

Schenkkan has cast his sequel with more than 40 historical figures, along with a gaggle of politicos and activists. This cacophony at times confuses more than it clarifies, and sound bites often substitute for flesh-and-blood characters.

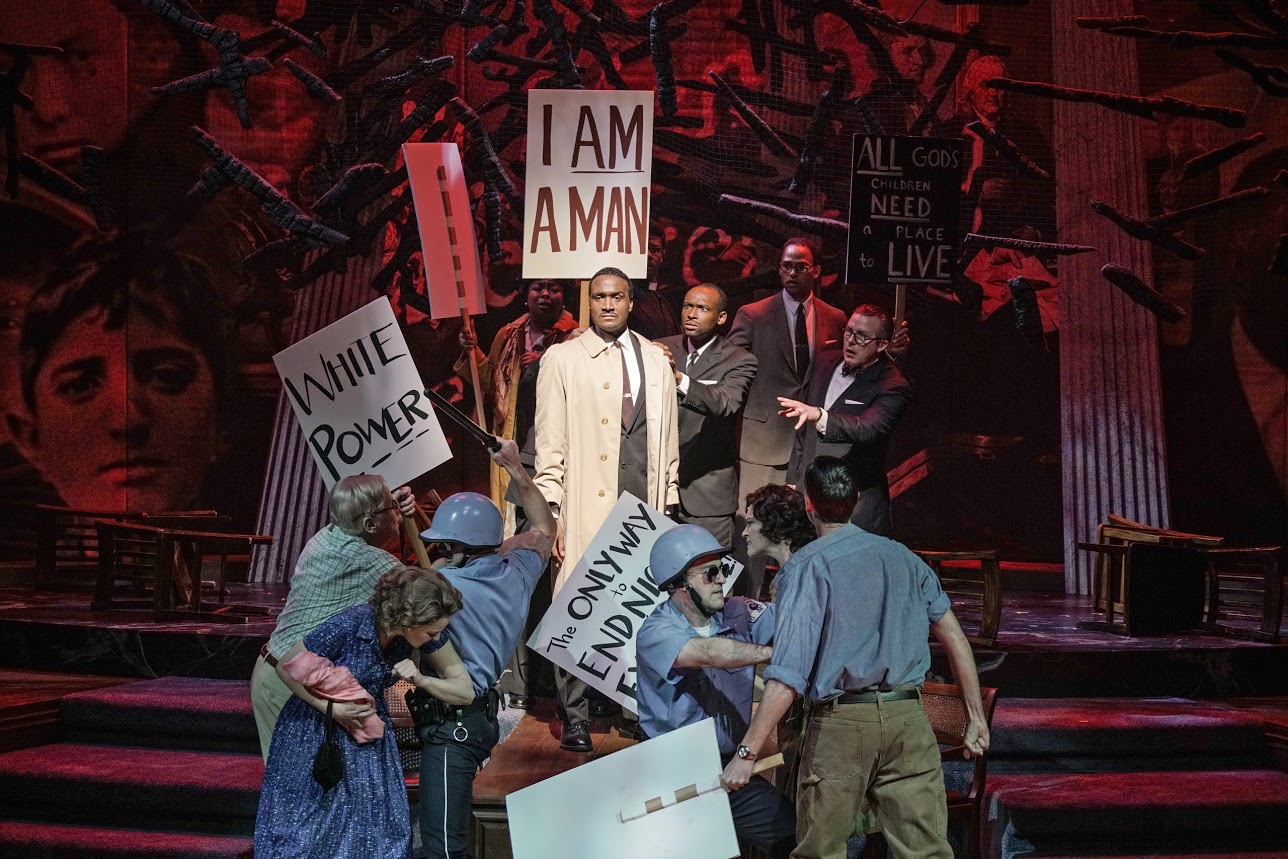

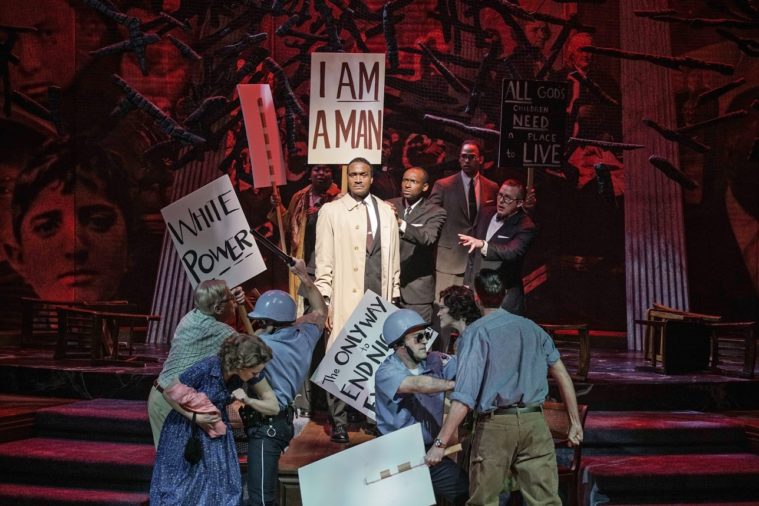

The playwright focuses on the events that defined LBJ’s presidency: Selma-to-Montgomery marches; the budget fights to fund Great Society programs; the human toll of the Vietnam War; and finally, Johnson’s decision to not run for re-election. Much of this has been covered in history books, the media and films. And while we have a front-row seat to the inner sanctum of the Johnson White House, little new is uncovered, and few are the insights into LBJ’s private persona and decision-making.

Schenkkan has cast his sequel with more than 40 historical figures, along with a gaggle of politicos and activists. This cacophony at times confuses more than it clarifies.

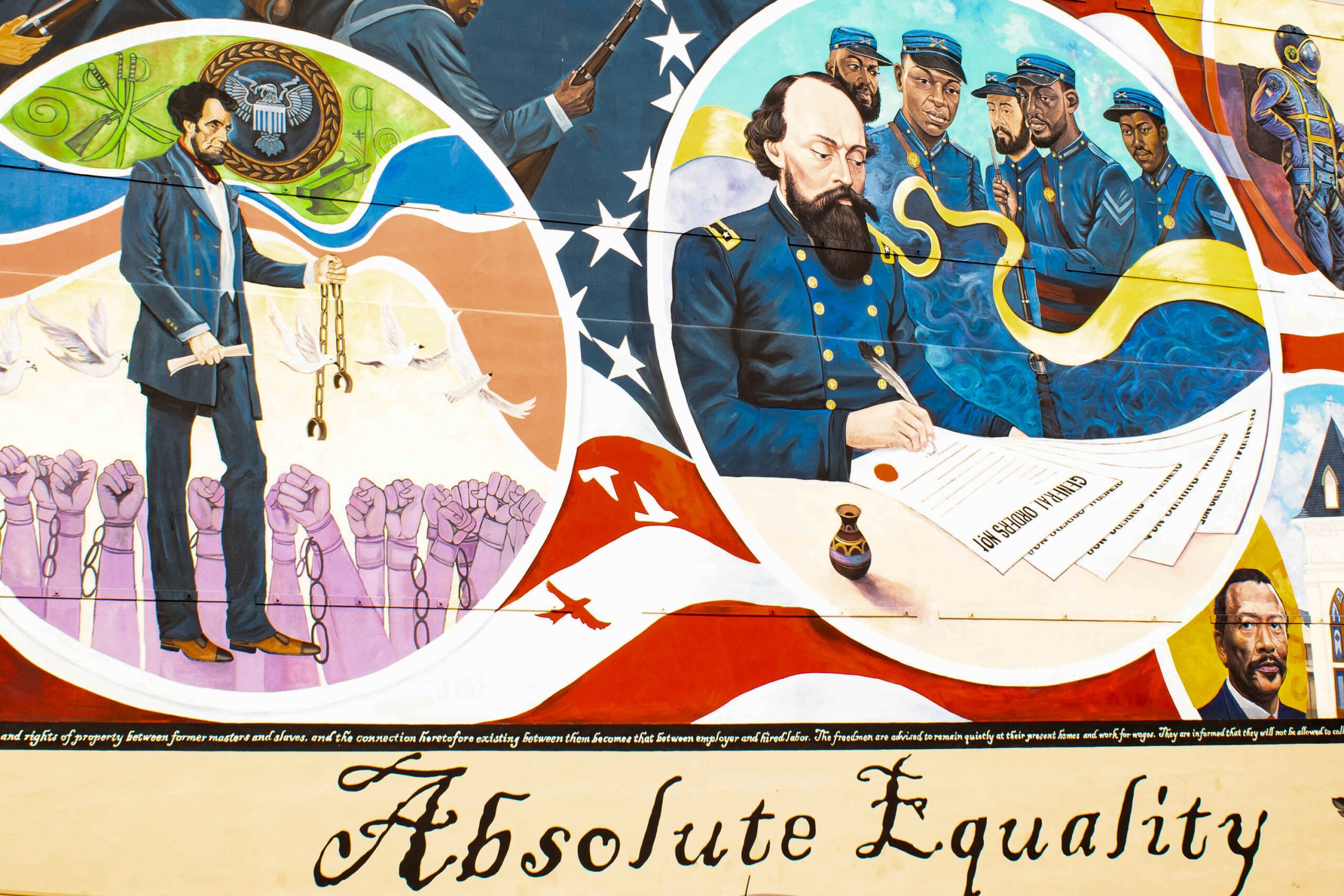

I had high hopes for this production, having seen All the Way on Broadway with the mesmerizing Bryan Cranston as LBJ. (Both the play and Cranston won Tonys). A high point is the majestic stage design: Three billboard panels depict the Founding Fathers, the Mexican-American schoolchildren LBJ taught in Cotulla, Texas, and the powerful image of Rosa Parks. My expectations were later dashed, for neither women nor Latinos are portrayed in major roles.

The Civil Rights Act was for all disenfranchised citizens, yet only black and white characters inhabit this play. It also prohibited discrimination in the workplace based on gender, yet Schenkkan makes nary a mention of the nascent women’s movement. Instead, the female characters are wives of politicos or secretaries serving as sounding boards.

Nor is there a gadfly or Shakespearean fool to question the folly of Vietnam. At one point, Johnson wearily tells Lady Bird, “I don’t understand why they hate me so much.” Might he not ask that of a Latino family whose drafted son never came home? Instead, we have LBJ’s son-in-law, Marine Captain Charles Robb, bringing the false news that “we are winning the war” to Johnson. We do view a tally of the growing numbers of American casualties in Vietnam, but statistics do not put a face on the horror.

Where is the valiant Eartha Kitt confronting Lady Bird and speaking truth to power and the disproportionate number of blacks and Latinos serving and dying in Vietnam? Where are Cesar Chavez and the Texas farmworkers descending on the state Capitol petitioning for fair wages, better working conditions and protection from the Texas Rangers, who were often as vicious as state troopers in Mississippi and Georgia?

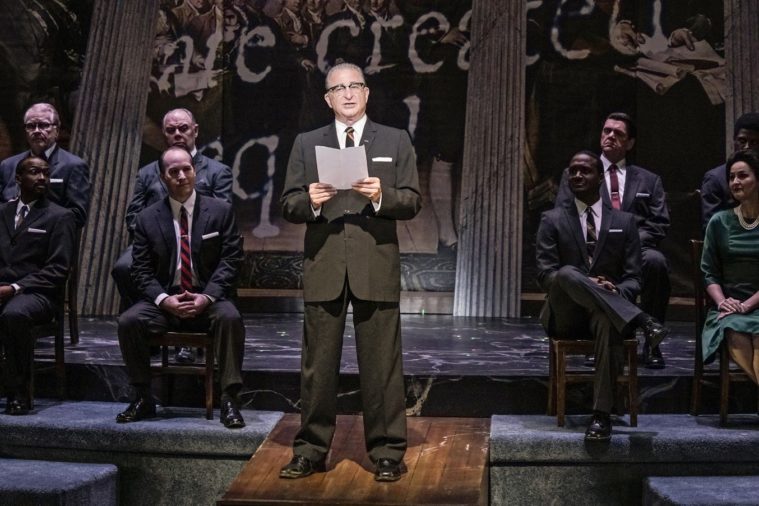

When Johnson delivers his speech about the suspension of the bombing in North Vietnam, he also announces he will not run for re-election. We can only conjecture as to why this man whose compassion was often mitigated by his ambition forfeited his lifelong dream.

Bill Moyers once said LBJ was “13 of the most interesting people” he’d ever met, yet setting the action in the Oval Office offers an incomplete rendering of this flawed giant. By sticking too close to history instead of the magic of inspiration that theater can provide, by not allowing Johnson a necessary moment of self-reflection, Schenkkan gives him a pass by having his successor Richard Nixon come to the White House, stealing the thunder from LBJ.

This denouement eerily evokes Trump’s Inauguration Day meeting with Obama. When LBJ asks Nixon what he plans to do now that he’s in charge, Nixon echoes Trump’s bombast in a heavy-handed line: “The same thing as you, Mr. President; I’m going to change this country. I’m going to make it great again.”

By injecting today’s politics in this way, more didactic than thought-provoking, Lyndon Baines Johnson exits not with a bang but a whimper: “Let’s go home, Bird!”

LBJ and we, the people of the Great Society, deserve better.